At MIGS25, the question was simple: can Canada stay one of the best places to make games?

As we mentioned in our preview, there is a sense that the spotlight at this year’s Montréal International Game Summit’s had shifted slightly toward the people making games, as well as the fragile business structures that keep them going.

Warmly ensconced inside its new Grand Quay venue, safe from the snow and slush of Montréal in November, MIGS25 feels like a thriving campus of ideas and opportunity. The traditional B2B core is complemented by an Indie Pod full of game prototypes and demos, conference rooms focused on development and developer adjacent talks, and an expo that pulls together the infrastructure around games. Tool makers, service companies, platforms and trade bodies mingle alongside studios of all sizes.

Despite the increased footprint of this year’s venue, it does not take long for faces in the crowd to become familiar. Compared to louder, more chaotic conventions, MIGS feels relaxed but never sleepy. There is business to be done, after all.

This year, two sessions in particular painted a picture of where the Canadian games industry is heading. One came from studio founders and publishers wrestling with short term realities. The other came from the industry association looking at the long game.

Reality Check

One of the recurring sentiments at MIGS25 was that the last eighteen months have been a reality check. This sentiment was front of mind in a panel titled Visions of the Future for the Canadian Video Game Business that brought together Christopher Chancey of Indie Asylum, Lysane Perreault from Norsfell, Joshua Nilson of Maskwa Games, and moderator John Nguyen from Xsolla.

During the pandemic, studios ramped up to match a surge in player interest. Layoffs across the industry, including in Canada, have marked the end of that boom. With players split between thousands of games, numerous social platforms, and every streaming service under the sun, capturing attention is now just as important as revenue.

“It used to be you’d ship a game, and have the top banner on Steam for three days straight because there were 300 games that shipped that year. Now there’s 15,000 games shipping on Steam every year,” Chancey says.

The response from Canadian studios, he says, has been a shift in mindset toward commercial awareness and building long term sustainable businesses.

“People are actually trying to make a business out of it for the first time in a long time. Because the opportunities are harder to get, people are trying to do a really good job of selecting the right game, and the right audience, from the get-go. The biggest change I’ve seen, is people trying to have more of a commercial mentality when they’re starting studios or starting projects.”

A more considered approach is also visible in more established studios. Perreault describes it as “the big freeze.” At Norsfell, the success of Tribes of Midgard led to rapid growth, but the studio decided to pump the brakes and not grow too large too quickly.

“We decided to stop recruiting. We have to stabilize. We have to check what is going on and make clear decisions and intelligent decisions,” she says.

Chancey adds that mid-sized studios of around thirty people – and the budgets these studios demand – have become the least comfortable place to be.

“Sub one million is comfortable,” he says. “And over 10 million, you’ll have some bigger tickets. But in between, nobody is really investing in that zone anymore. Are we going to be Disney? Or are we going to be A24? It’s really uncomfortable to be in between.”

Funding has not disappeared, but it is changing shape. Instead of betting big on one ambitious production, Chancey says that investors are more cautious, more metrics driven, and much more likely to spread smaller investments across multiple projects. Business sustainability is just as important as a good game idea.

Nilson cites his own experience as a publisher at the micro level. His focus is on developing small, nimble teams, building them up slowly and mentoring them on how to operate as businesses, not just creative outfits.

“We write $25,000 checks to get indigenous entrepreneurs started. But it’s not the check that matters,” he says. “It’s that strategy. It’s not just about making a great game.”

Perreault also encourages teams to think small and ship fast, so they can confront the commercial realities of game development more quickly.

“Build a tiny team, take your next project as a product, try to find a niche,” she says. “Or find a simple idea, and deliver it very efficiently.”

The panel’s advice for new studios was firm but encouraging. Chancey says too many founders start at the top with self expression and forget to build a solid base for their studio. That foundation, he says, should include market research, developing a deep understanding of genre conventions, knowing your audience, and thinking about scope.

In a country famed for its politeness, Nilson adds that Canadian creators need more honest criticism of their ideas.

“Make sure your feedback isn’t your friends,” he urges. “We need to make sure we’re still kind, but we need to make sure we’re blunt with our feedback.”

And, if Canada has one other glaring weakness, the panel agrees that it’s in the marketing and commercialisation of the products it makes.

“Everybody sees us on the planet as one of the best places to make games,” Chancey says. “But, we really suck at selling games.”

He argues that tax incentives and big studio investments have turned Canada into a production factory, while strategic and marketing decisions are often made in Europe, Japan, and the US. The result is a workforce that does not always have the necessary depth of experience when it comes to selling games from Canada.

Nguyen adds that studios should stop treating marketers as outsiders or late stage additions.

“I wish us to embrace and bring marketers, commerce, business people into our studios and treat them like any other UX guy or animator. Really integrate them into your team from the very beginning.”

Despite the challenging landscape, there was a cautious optimism on the panel that conditions are starting to thaw. Interest rates are easing, some funds are returning, and new Canadian publishers are starting to appear. The skills and ambition are clearly there, and what the Canadian games industry needs now are the right tools and the right support. The structural problems are real, but they are not insurmountable.

Power up

Enter Paul Fogolin, President and CEO of the Entertainment Software Association of Canada, who took the stage to present Canada’s Video Game Industry – From Strength to Staying Power. Where the earlier panel was a conversation among founders trying to help the next generation of creators start off, this was the policy and numbers view. If the structural issues can be fixed, perhaps this is where it starts.

“While you’re all working hard to make the games that are played by millions of people around the world,” Fogolin says, “we’re working behind the scenes to ensure that this country remains a fantastic place to make games.”

The ESAC represents more than twenty companies with a presence in Canada, including console makers, major studios, and large publishers such as Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft, Ubisoft, Behaviour, Gameloft, and EA. The association’s work includes meeting policy makers, commissioning research, running events on Parliament Hill, and providing tools around ratings, trust, and safety.

It’s not uncommon to hear that video games are “bigger than music, film, and TV combined”, but Fogolin notes that governments and media still often react with surprise when they find out. Canada’s contribution to that market is significant, with ESAC’s latest economic impact report stating that there are more than 34,000 jobs in the Canadian games industry across 821 studios. Altogether, the sector contributes 5.1 billion dollars to Canada’s GDP.

Fogolin says that talent is the bedrock of the industry, with the association emphasising a push for more investment in education and training. Tax credits and other incentives have also been crucial, but the challenge now is to keep them competitive and predictable, and to adapt them to new models like games as a service. He also stresses how important it is to maintain a mix of global investment and Canadian owned studios.

“Part of the Canadian industry strength is we’re a mix of Canadian owned indies and investment from global companies.”

Regulation should support both, Fogolin argues, by encouraging big companies to invest while giving local studios the room to grow, own their IP and take creative risks.

“Our industry sits at the nexus of innovation, culture, and economics,” he says. This makes the industry unique but also harder for government to decide on who should lead new initiatives.

“I think there is room and time for a national strategy for the industry that brings the federal government and provinces together and says, look, this is a key strategic economic space, a key strategic cultural space. And so we need to all be at the table to promote that.”

Crisis and Confidence

Taken together, the two sessions at MIGS told a clear story. On one side, you have studio heads and entrepreneurs working through a period of intense pressure. At the same time, you have the industry association demonstrating that Canada is still a global leader, with high quality jobs, strong exports and a compelling case to make to government and the public.

Both conversations acknowledged the same reality. Canada is very good at making games. To keep doing that, it needs to get much better at everything around them. That means more domestic publishers and investors. More incubators and accelerators. More collaboration across provinces. More honest feedback. More marketing and business insights. And more joined up thinking from the federal government.

But underneath all of that, one other thing remains: the simple joy of making something that connects with people.

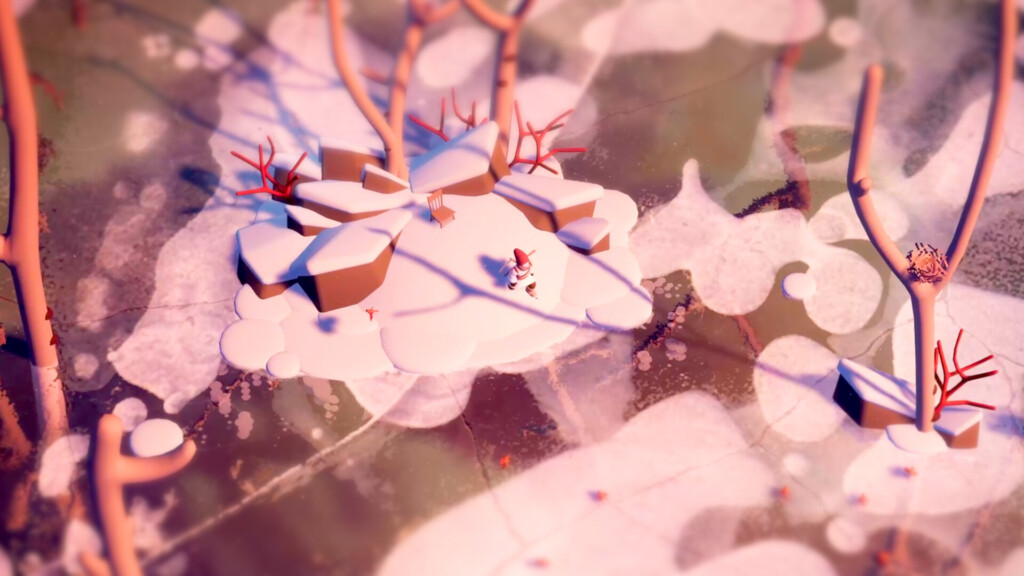

At this year’s Indie Pitch Competition, a collection of locally made games embodied that fact. Whether it was the simple pleasure of skating across the frozen wilds in North Shore, the golden hour slice-of-life tale of RollerGirl, or the Ueda-inspired survival adventure of Architects of Giants, these promising games were beautifully crafted reminders of why everyone was is at MIGS in the first place.

Walking out of the conference and back into the snowy chill of Old Montréal, it was hard not to feel warmed by the mood at MIGS25. There was recognition that things are tough, and that some old assumptions are gone for good. But alongside that, there was a confidence that Canada has everything it needs to write its next chapter.