In the midst of a global pandemic, virtual escapism has never felt so urgent.

Our bodies are restricted to social bubbles, our eyes witness the same handful of surroundings and our minds are desperate for change. Video games are a guardian angel for many (myself included) during this global pandemic, offering sights and sounds that are now physically out of reach. Why on earth, then, would I choose to spend my time playing horror games? Surely all one needs for their daily injection of fear is a split-second glimpse at the headlines, but lockdown hasn’t sanitised these games of their scares; it’s elevated them.

All video games fundamentally grant their players navigation of virtual spaces. The familiarity of basic level design often leads players into taking basic elements for granted: floors, walls, worlds. As quarantine protocols continuously rewrite our understanding of real-world space, horror games similarly possess the eerie ability to rewrite their own digital worlds.

Silent Hill and claustrophobia practically go hand-in-hand. Ever since the fog-swept town’s introduction in 1999, Konami’s horror franchise has focused on intertwining space and narrative through symbolism and masterful design. Silent Hill 4: The Room may be the series’ crown jewel in this regard, despite its various debatable shortcomings in other departments.

From the moment Silent Hill 4 begins, something is off. The player is not in Silent Hill; they are in Henry Townshend’s apartment in the distant South Ashfield. The player cannot see Henry; the introduction is radically presented in first-person (long before P.T.). The player is not alone; something is in this room with you. Whilst it makes for a bland subtitle, it’s hard to overstate the importance of The Room to Silent Hill 4s execution. The narrative conceit itself is uncomfortably similar to real-world events with Henry inexplicably trapped in his apartment under literal lock-and-key.

During his confinement, Henry embraces his inner L.B. Jefferies and witnesses the ongoing narrative as a passive observer. Residents enact their daily routines, ambulance sirens wail from the adjacent streets and only his next-door neighbour Eileen seems concerned about Henry’s absence. These narrative events are exclusively presented through restrictive means: windows, radios and even secret peepholes in the walls. Silent Hill 4 is constantly communicating information claustrophobically.

Lockdown transforms our safe spaces into repetitive and actively irritating environments. My bedroom is cosy and familiar, but it’s simultaneously an active reminder of my own physical limitations. It’s not just my safe space, but my only space. Few games tap into this incredibly specific sensation like Silent Hill 4. Henry’s apartment initially serves as a traditional hub world containing the sole save point, a storage chest and even heals you over time. Yet, as Henry continues his visits to alternate realities through the irrefutably demonic portal that manifests in his bathroom, his room, in turn, becomes infected.

Around the halfway mark, The Room abruptly shifts from the game’s only safe space to its most threatening. Film grain and aggressive vignettes invade the first-person camera, unsettling noises disturb the ambience and Henry now takes damage if he lingers for too long. It’s a frustrating but effective representation of how perceptions of familiar spaces can be sharply altered by circumstances beyond our control. Henry might not be facing a literal pandemic, but it’s hard to ignore the presence of ghosts breaking through his once-solid walls.

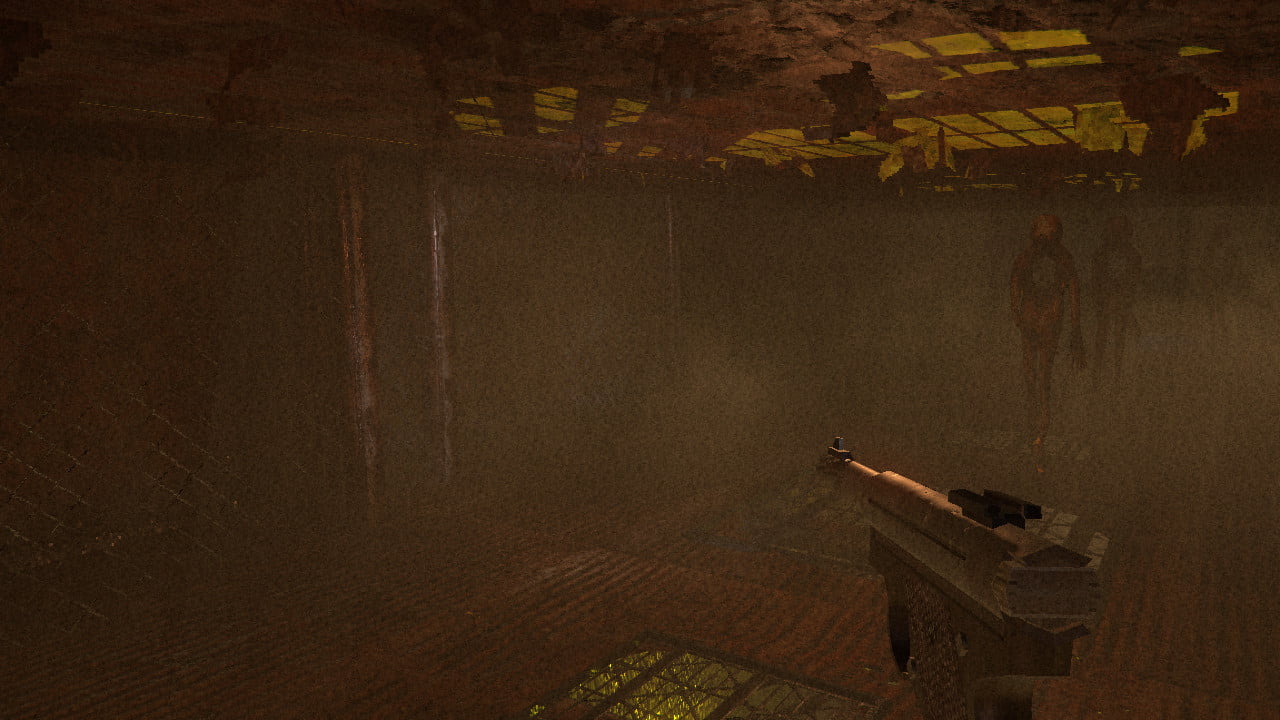

This is taken one step further in Akuma Kira’s bone-shivering Lost in Vivo, a lo-fi indie horror title wearing its Silent Hill influences on its sleeve. After losing their dog in the sewers, the protagonist abandons the outside world for an underground hell, one that grows only more surreal and suffocating over time. The tight sewer tunnels of its first act only scratch the surface of Lost in Vivo’s claustrophobic nightmares. Alongside the prerequisite abundance of narrow corridors and unnatural geography, Lost in Vivo has high ambitions in expressing an internalised confinement. In the vein of Silent Hill 2’s made-for-measure monsters, Lost in Vivo weaponises its spaces against the protagonist’s strongest anxiety: their own body.

In one striking sequence, the player swallows an apple only to be met by prison bars. The only way to pass through is to vomit up the apple. What lies in the room beyond? The apple restored on the pedestal. The solution? Those prison bars were never real, but false projections designed to taunt and intimidate. Symbolism in level design isn’t anything new, but this example nonetheless stands as an innovative example of externalising internal conflicts. Even if the body can’t be left, self-perception can be actively changed. Physical prison bars can become invisible. The protagonist’s body operates as the inverse of Henry’s apartment; the experience of horror is a healing one.

If scepticism regarding the solidity of Lost in Vivo’s environments begins to settle in, that’s perfectly natural. Kira’s enemy behaviours are among the most unique I’ve experienced in a horror title for one simple reason – they don’t obey the laws of space. Sprites clipping through walls would usually be perceived as a glitch, but they’re a bonafide feature here. Plenty of Lost in Vivo’s antagonists disappear and reappear at will, some merging into the ground or unexpectedly crawling up ladders in pursuit. One lethal monster is immobile but can freely teleport, even inside crates or doorways forcing players to be unusually perceptive.

As the player acknowledges entities acting outside the parameters of their first-person camera, even the computer monitor begins to feel claustrophobic. Sound – not sight – is the critical tool in the player’s arsenal. A novel implementation of positional audio acts as a makeshift antidote to the visual claustrophobia, giving players the resources to detect unseen enemies and pathways through snaking drains. My experience of Lost in Vivo during lockdown enhanced its frights, but also persuasively conveyed the emotional and practical tools to combat those induced feelings of isolation.

Horror has consistently revolved around catharsis, more so than fear. Silent Hill 4 and Lost in Vivo both accurately depict the intensity of extreme claustrophobic scenarios, but amidst the equally extreme current climate, they also offer valuable moments of self-examination. Through Silent Hill 4, I grew to appreciate the delicacy of our situation. Through Lost in Vivo, I understood that sometimes we need to lose our understanding of normalcy to find a better alternative.

At times, these games heightened my fear and paranoia as intended. But against the backdrop of a real-life crisis they told me that, ultimately, everything is going to be okay.

You should definitely follow Thumbsticks on Twitter for more gaming features. Enjoyed this long read? Support us on Patreon or buy us a coffee to enable more of it.