Independence, in its most basic form, is quite a straightforward concept to grasp.

It describes the state of being independent from any other ruling body or party, and in purely historical and political terms it’s easy to point to examples: The Americans declaring independence from the British; the Irish winning independence from the British; the Australians gaining independence from the British; the Indians being granted independence from the British… wow, we really were colonial bastards, weren’t we? It’s no wonder we always play the bad guys in movies.

Independence and the creative arts

An independent film for example is one that is created, financed and distributed without the support of one of the six major Hollywood studios – Warner, Disney, Columbia, Universal, Fox and Paramount – but what defines an independent record is a little more difficult to quantify. Obviously a record produced by a major label (like Sony or EMI) instantly precludes an artist from being independent, but many smaller companies or vanity labels (record labels that are run by musicians whose own output belongs to a major label) are often financially backed by the major players, usually with less than a 50% stake to try to preserve neutrality from the parent.

It’s certainly a far cry from the DIY labels of the punk era and nowadays many ‘independent’ record labels are in themselves fair-sized businesses. Over time, as the independent labels have grown bigger the true nature of the indie is returning to its DIY punk roots, but instead of photocopying cassette inserts at the local newsagents and trying to sell your record to punters after a gig, the digital publishing revolution means anyone virtually can have music for sale via digital services.

This democratisation of the publishing process has another side-effect, though: the rise of the enthusiastic amateur. When you’re in a band and you’re just starting out, playing to empty pubs for ‘the exposure’ and dreaming that one day you’re going to make it big, it’s a lot easier to tell yourself that you’re an indie band who just hasn’t broken the big time yet. It also sounds a lot cooler to tell other people you’re an independent band than admit that you’re amateurs, and the presence of an EP on iTunes – made possible by the digital publishing revolution – merely serves to validate these lofty claims.

Unfortunately because local bands are often our first exposure to the indie phenomenon, and most of them are of the enthusiastic amateur variety, the world seems to have developed an internal equivalence that indie and amateur are one and the same.

Independence and video games

When you look at the world of indie video game development, it’s a similar story to the perception of indie music.

If asked to rattle off a list of independent games we’d all probably go to the same places – the likes of Braid, World of Goo, Super Meat Boy, Hotline Miami – and subconsciously, we’re drawn to the games that look and feel like our brains tell us indie games are supposed to. They might have simplistic pixel art graphics or retro gameplay mechanics, or they might just be really short, but something deep-seated is telling you that – even though they might be brilliant games – because they’re independent, they’re in some way deficient or lacking.

When you’re an independent developer you might find that the retro visuals are all you can manage on a limited budget, or it may well have been a conscious stylistic choice and that’s how the game would look with unlimited funds but either way, to some consumers it serves as a positive affirmation that this game is somehow something poorer as a result. Your game might be shorter because (without major publisher backing) you just needed to get your game out there and earning you some money so you could move onto the next one, or that might just be the length it was always supposed to be, but to some it would still serve as an indicator that indie games are somehow less than those from major publishers.

That’s not to say that all indie development is professional of course, and it’s certainly plagued with as many enthusiastic (or misguided) amateurs as the indie music scene, but to write all indie games off as amateurish based on preconceptions of lower budgets or simpler styles would be sadly missing the point. It’s also worth mentioning that not all indie games look like the stereotype: the likes of Assetto Corsa, No Man’s Sky, Firewatch and SOMA all look and feel every bit like they’re come from a major studio but they’re all indie games, every last one of them.

Exceptions aside, all of this unfortunately feeds back into the fallacy that independence equals amateurism, and a perception of indie games as amateur efforts. As a collective cohort video game consumers are a tough bunch to please at the best of times, and one of the key methods of placating the masses has been to show deference to collective opinion of indie games by aggressively pricing your title.

The race to the bottom

Remember the good old days, where you could walk into a shop with a crisp £5 note and walk out with four brand new video games, a bottle of Tizer and a bag of pickled onion Monster Munch? (Americans, that’s roughly equivalent to $8 for four games, a bottle of root beer and some Funyuns.)

No? You don’t? Me neither. Playing video games has always been something of an expensive hobby, that usually involved saving up weeks of magazine delivery money to be able to pick up a second-hand game, or several months if I fancied something brand new and with cellophane on it.

Nowadays though you literally can pick up four games, a fizzy drink and some potato-based snacks for a fiver, thanks to digital distribution. The advent of 99c games on the various mobile app stores, flash sales on Steam and name-your-own-price charity bundles have left consumers genuinely feeling like they can get something for (virtually) nothing; if you’re prepared to suffer a few adverts, or be painfully hamstrung by not paying for microtransactions, you literally can game for free.

What this unfortunately means for the indie developers, in a world where – through no fault of their own, or their work – their output may be considered amateurish by your average consumer, is that they have to chase an ever-dwindling price point in order to get consumers to give their games a shot, both as their own value proposition and competing against the clamour of digitial distribution. Meanwhile only the tripley-est of AAA titles with tangible, physical copies can seemingly justify a $60 price tag; when was the last time one of those disappointed?

This bargain bin race to the bottom has ultimately put indie developers in an uncomfortable game of chicken, in which they have to price their games so low (and know the price will drop again, with sales) to generate interest and make it feel like a value proposition for ‘just’ an indie game, while at the same time trying to ensure they can pay their bills and fund their next project. I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t have any idea when to blink; it’s no wonder that the average indie developer earns less than $12,000 a year.

Picking a fair price

Last week indie developer Jonathan Blow upset many, many people by pricing his new game – The Witness – at $40 US.

The internet aggrosphere felt this price was outrageous for an indie game. Blow’s first release, the charming and extremely clever Braid – an admirable first effort that is every bit what you would expect an indie game to be like – only cost $15 and has sold over a million copies on Steam to date. It has spent a large portion of that time on sale though and its average price is probably closer to the 10$ mark; so why on earth should his new game cost four times as much?

People were incensed. This wasn’t what they were expecting at all. They felt like the money Blow made from Braid – which he absolutely has poured every cent into making The Witness, by all accounts – should have somehow cushioned them from such a steep price increase. This just isn’t what an indie game is supposed to cost.

To address those concerns, let’s stop and examine what’s on offer here for a moment.

Braid – Jonathan Blow’s previous game and the yardstick to which many will judge his future efforts – was a 2D platformer, put together primarily by Blow himself without any help (other than with the art). It looked indie, it felt indie; hell, it’s basically grown into the very definition of what an indie game looks like to our consumer sensibilities. It also only takes about six hours to complete.

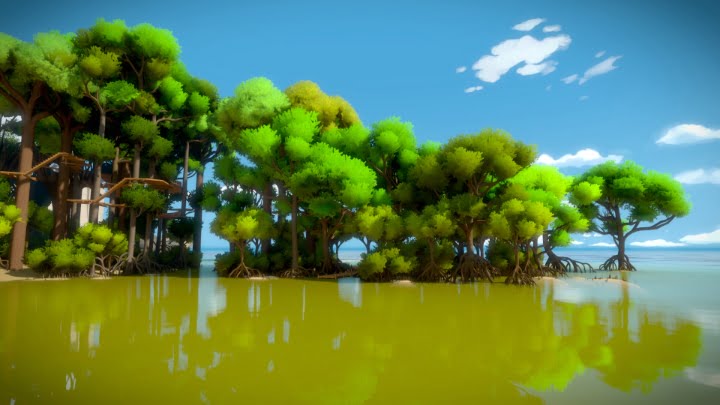

The Witness – Blow’s latest effort – is an immersive 3D puzzle adventure game with beautiful environments, animation and sound, that has been put together by a team of around fifteen people (including a mix of full-time staff and contractors). It looks beautiful, by all accounts it plays wonderfully, and crucially is a little bit longer than Braid… The Witness is actually around seventy hours (yes, 70) or more if you’re trying to find all the secrets and investigate every square inch of the mysterious island.

So The Witness is around ten times longer than Braid, was put together by a much bigger team (who all need to be paid and looked after) and it makes for a wonderful experience… so why people are still complaining that it costs too much?

The value proposition and the stigma of indie

When you compare the value on offer by The Witness against the completion statistics* of some of the major AAA releases in recent months, it makes for interesting reading:

- The Witness – 70 hours/$40 = $0.57 per hour.

- Fallout 4 – 66 hours/$60 = $0.91 per hour.

- Assassin’s Creed Syndicate – 32 hours / $60 = $1.86 per hour.

- Rise of the Tomb Raider – 17 hours / $60 = $3.53 per hour.

- Halo 5: Guardians – 10 hours / $60 = $6.00 per hour.

- Call of Duty: Black Ops III – 9 hours / $60 = $6.66 per hour.

*Completion times based on ‘main + extra’ values on HowLongToBeat.com.

It’s a similar story if you plot the completion times of shorter-yet-cheaper indie games – the $10-20 efforts – against the AAA contenders. Only the very longest of the big budget games like Fallout 4 or Metal Gear Solid V, or the unusually low-priced (like Life is Strange at around $1.25 per hour) can really compete with indie games for value.

Perhaps the biggest issue The Witness faces then, with regards to pricing and ultimately consumer perception, is the fact that Jonathan Blow’s name – and by extension, memories of Braid – are intrinsically interwoven into the project. It gives the impression to the casual observer that this is yet another short and cheap indie release, but offered at a price closer to that of the big budget AAA titles.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t compute against the indie = amateur impression that’s so hard for us to shake.

The bottom line

If The Witness came from any major publisher, or even from an indie studio standing behind a major publisher like Unravel (developed by Coldwood Interactive/published by EA) or Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (developed by The Chinese Room/published by Sony) then nobody would even bat an eyelid at its $40 price tag; in actual fact, they’d be heaping praise on how nice it was to see a new release coming in at less than $60. Perhaps if it came as a tangible, physical release rather than digital-only, that would do more to help consumers feel like they’re purchasing something substantial.

Unfortunately, the hard-to-shake impression that indie development is amateur development – combined with the very public face of Jonathan Blow as a perceived figurehead of indie development – has led to the excellent value proposition of The Witness being quagmired in online bickering and finger pointing, and overshadowed what looks to be an incredibly successful and well-received game.

The bottom line is, if you don’t agree with Blow’s pricing for The Witness then you don’t have to pay it and nobody’s forcing you; and there’s really no need to wail and whine all over social media and forums about it. Get on with your lives, and let everyone else get on with theirs.

If you really do want to play The Witness but don’t think it’s worth $40 – which is frankly a little hard to comprehend and maybe you need to take a long, hard look at yourself – then you could always wait for the inevitable race to the bottom that beleaguers indie publishing, and wait for the ridiculously low sale prices. They will be coming, sooner or later.

Pick up The Witness from the Steam or PlayStation stores.