It’s a trope so overused it borders on cliché, but perhaps the amnesiac protagonist route is so well-trodden precisely because it is so effective?

Plato theorised that we are all born with all the knowledge in the world – we simply need to remember it. Marie Antionette once said, “There is nothing new except what has been forgotten.”

Playing with memory and memory loss is a staple of media, and always has been. In The Madness of Hercules by the ancient Greek poet, Euripides, the hero is gripped with madness and can’t remember his own family. In this crazed state, he murders them all and must make amends by undertaking his famous 12 labours. In film it’s been used in every genre – from action movies like Total Recall to romcoms like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Amnesia is also an absolute staple of soap operas – the Australian mainstay of Neighbours uses it frequently. One famous example was in 2002 when fan-favourite Susan slipped on some spilt milk (queue obvious jokes) and lost 3 decades worth of memories. That other beloved form of soap opera, wrestling, also uses amnesia. In 1993 Cactus Jack was powerbombed by Big Van Vader into the concrete floor of the stadium. The character was institutionalised, eventually escaping his mental hospital and developing amnesia before eventually returning to the ring.

Video games are no exception to this ancient trend – and though amnesia plotlines have a reputation for being lazy and schlocky, I am here to defend them. So from Hercules to Cactus Jack to Link – what makes memory loss and retrieval so appealing?

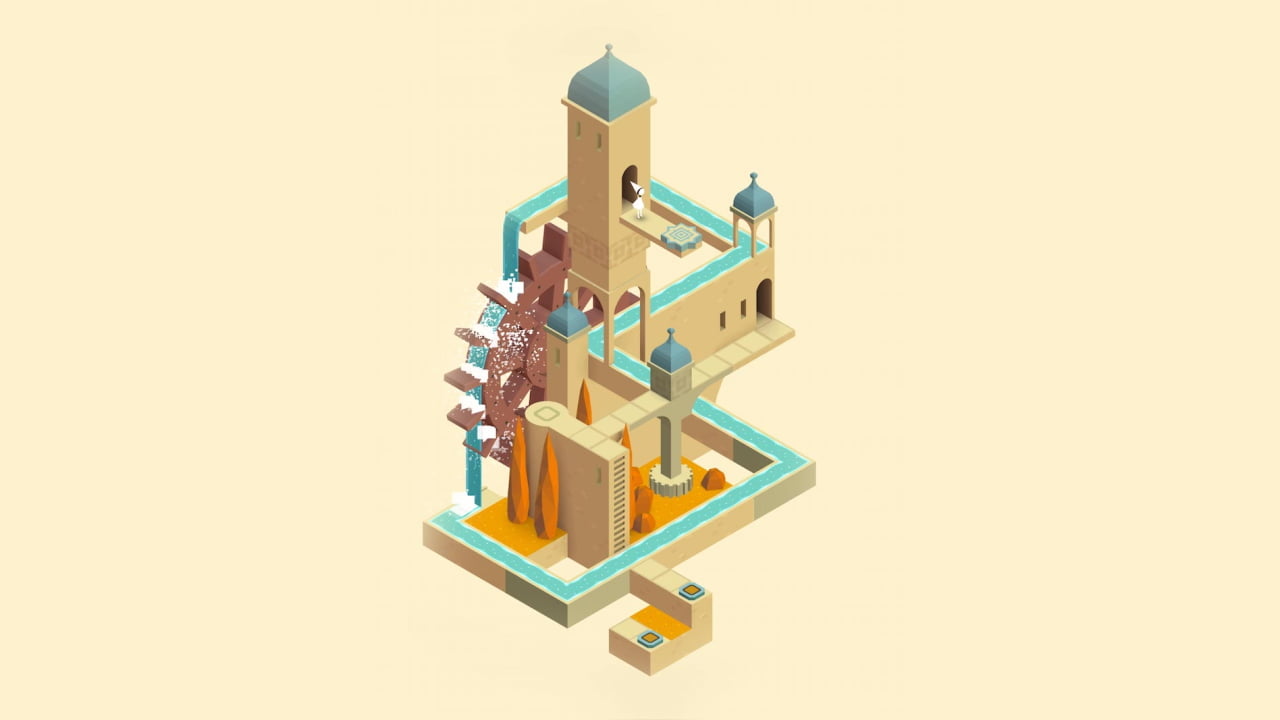

Let’s start with Monument Valley. This British app-game won a Bafta in 2015 for Best British Game. It’s deceptively simple – you must twist and turn the Escher-inspired architecture to navigate the beautiful and geometric landscapes. But as we progress through the first level we are told that Princess Ida must return all the Sacred Geometry that she’s stolen. Just like Hercules, Ida must undertake her own series of labour. We follow Ida on her emotional journey – the shame of discovering her crime, the loneliness of the empty cities, the fear of the antagonistic crows and eventually the joy of redemption and release.

In 1922 Proust wrote In Search of Lost Time, which includes his famous “madeleine moment”:

“No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me […] And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings […] my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. And all from my cup of tea.”

This hugely evocative moment has been referenced and resurrected many times – most famously in the Pixar movie, Ratatouille, where the food critic Anton Ego is instantly transported back to his rural childhood with just one bite of the eponymous dish.

Old Man’s Journey, like Monument Valley, is another literal voyage into memory and emotion. Like Proust with his madeleines, the player character of this game has memories periodically triggered as you traverse the dreamy landscape. We all know this feeling – a long-forgotten memory that floods our minds, transporting us into a past moment. (As Proust said: “And suddenly the memory revealed itself”.)

This game perfectly represents that feeling. The memory washes over the screen, the sounds and colours so evocative of the past moment. But it is also fixed and nearly static, a fragment we can recall but can’t interact with. As Proust was in search of lost time, so is the main character in Old Man’s Journey. We already know where he has ended up – old and alone on the sea shore – but as we walk with him we uncover that lost time and what has come before.

The Legend of Zelda is one of the most well-recognised legacy properties in the games world. But significantly we know it as Zelda, and it’s her name we remember, even as we take up another game to play as Link. Link is left deliberately blank so that we can project ourselves into him. Scott McCloud, in his excellent book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, he writes: “When you look at a photo or realistic drawing of a face, you see it as the face of another. But when you enter the world of the cartoon , you see yourself.”

The blankness of Link, the simplicity of the sketched out person, leaves room for projection. Enter: The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

This is Link at his most blank, most characterless. As the game begins he is stripped of even his iconic outfit – as well as all of his memories. Even the marketing of the game plays into this, the website stating: “Forget everything you know about The Legend of Zelda games”. Forget what came before, just as Link has.

Gradually he recovers his identity, his memories, even the landscape opens up and unfolds before him as he recovers memories. Critically we, the player, build our skills, knowledge and identity alongside Link. This mirroring leverages an enormous emotional payout at the game’s conclusion – good friends of mine wept at the close of Breath of the Wild.

Amnesia used in clumsy hands can be silly and schlocky. But when the rediscovery of memory is used with skill, it builds the closest of relationships between the player and the player character. The Tabula Rasa – or blank tablet – of the character allows us to project ourselves onto them. We discover the past and personality, abilities and history of the PC at the exact moment as the character themselves. We might be separated by the screen, but in that moment our minds are as one, the feelings evoked are perfectly in sync.

Roger Ebert once called cinema an “empathy machine” and games have the potential to create just as much, or even more, empathy for our main characters. Through amnesia plots, alongside the device of having us work to discover memories in tandem with the player character, video games are engineering a significant amount of empathy.

From the archive: Features we love given new life. Hannah’s essay on madeleine moments and amnesia in video games was first published on September 15, 2020.