At Develop:Brighton Alexis Kennedy, co-founder of Failbetter Games, spoke about the challenges of building non-linear stories.

The traditional modes of narrative structure have been defined through years of storytelling. We are all familiar with the three act structure, and templates such as the hero’s journey are ever present in today’s media. Games however, offer the scope to tell stories in a new way.

Failbetter Games has won plaudits for both Fallen London and Sunless Sea, two games intrinsically built around non-linear storytelling.

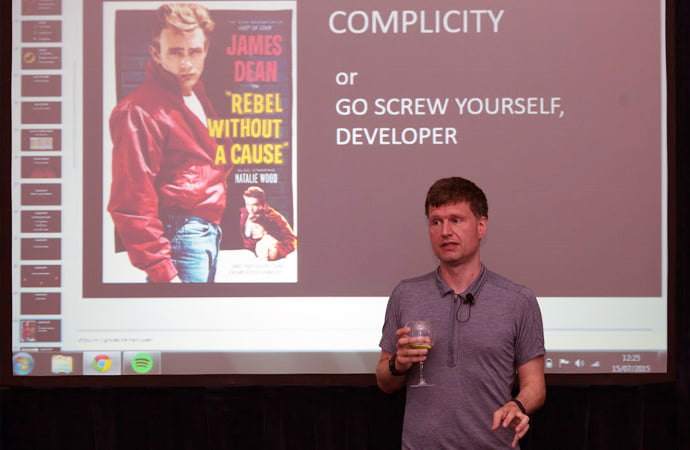

Kennedy began his talk by outlining the three pillars he sees as fundamental to non-linear narrative: choice, complicity and consequence. Of these, he says, the third is often seen as the most important.

“We still, as an industry and as gamers, focus too much on what comes after (choice). We think a story doesn’t mean anything if it doesn’t have significant consequences,” said Kennedy. “Players feel cheated if they don’t get sufficient consequences.”

Unfortunately creating a game with a large number of consequences is a huge devourer of resources.

“Consequence is the most valuable. And it is the most expensive,” said Kennedy. “The more alternate story states you have, the more you have to write, and that accelerates extraordinarily quickly.“

And the focus on consequence, by players and developers, can mean that the other pillars get neglected.

“For choice, the key thing is that moment before you actually make the decision, when you feel that fulcrum of having agency,” Kennedy explained. “Complicity is what you feel in the moment when you are making that choice…”

Complicity is the moment when the player can express that agency. Only when these two aspects work well can consequence work then effectively.

All well and good. But why bother with a choice-based story when traditional linear storytelling has served us well for so long? Kennedy believes it is a way of dealing with the last great resource squeeze; attention.

“It’s the thing we are all short of,” he says. “If your story is paying attention to the player, they are going to feel validated. Choice asks them to express themselves, complicity lets them express themselves, and consequence shows that your story has paid attention and responds to what the player wants.“

“If you are doing things that pay attention to the player, the player will care. If you are not – well – you are playing with yourself.”

Underpinning all of this is the theme of the game. The term ‘theme’ can mean different things to different people but for Kennedy it’s a fundamental component.

“The most important thing in game design, at an organic level, is making sure that the mechanics, aesthetics, and story all align along the same theme.”

The theme for Sunless Sea was in place right from the start – right there in the initial Kickstarter video – Loneliness, exploration and survival, and light and dark.

“Everything we did in the game pulled towards those choices,” says Kennedy. “The story pulled toward those choices.”

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/failbetter/sunless-sea/description

The temptation when creating non-linear stories is to throw in the kitchen sink. Kennedy explained that more is not necessarily better. A huge number of choices actually displays a lack of authorship.

“You’re being boring,” he said. “Because you’re not giving the player a story, you’re giving the player your own stream of consciousness. Pick your theme and find choices that reflect that theme and allow the player to express themselves.”

The key is to offer a limited number of choices but make then meaningful to the player so that they understand what they are being asked to do. Kennedy cites the worst type of choice you can find in a game.

- Left.

- Right.

- Straight on.

“People won’t know the difference between left, right and straight on, and they won’t care,” he explained.

Kennedy demonstrated how the same set of choices could be made more interesting if they also allowed the player to express themselves.Left could be an air vent, for a stealthy approach. Right, might require seducing a guard and the middle choice, an all guns blazing approach.

“Three choices is a nice number, two things that are opposed and one that is a bit of both. Five is even better, the sweet spot.”

Kennedy says that five choices offers a rich sense of engagement with the player. Although sometimes it also pays to show a player a restricted choice. This shows that the game is replayable and has been created with rigour and with real restrictions.

“The thing the player feels is up to them. The protagonist is the player. Not a character you have written.”

This means that you should never describe what the player must feel.

“Never tell a player why they have done something. Never tell them what they are supposed to feel,” says Kennedy. “They are feeling it.”

Describing how a player should feel breaks that long-written commandment; show not tell.

Kennedy also by highlighting one of the other aspects that story driven games have at their disposal.

“Nearly all games are fantasies of success. There are very few fantasies of failure. If you think about some of the most powerful books, plays, films a lot of them are tragedies. A lot of them show people disintegrating. And those people are magnetic while they are on the screen, or on the stage, or at the centre of the text,” he said.

”To allow the player to destroy themselves and make that seem cool – you are giving an experience you can’t get in a lot of places.”

To finish his talk Kennedy concluded with some sage writerly advice that is always relevant, what ever the medium: When it doubt, leave it out.

“The temptation is to write long and give people value for money. More is not always better. Say what you need to say and get out of the way.”

Main image credit: Develop:Brighton