Asobi Studio’s Astro Bot Rescue Mission is one of the highlights of Sony’s PlayStation VR platform, and probably one of the most engaging examples of virtual reality gaming to date.

The character of Astro Bot made an (unnamed) debut in Robot Rescue, one of the seven mini-games included in The Playroom VR. The collection was one of the best PlayStation VR experiences at launch, and player reception was so positive to Robot Rescue that the go-ahead was given to develop a full sequel in late 2016.

In his GDC 19 talk, The Making of Astro Bot Rescue Mission: Reinventing Platformers for VR, Sony’s Nicolas Doucet spoke about the some of the game’s design tenets.

Doucet’s talk covered all aspects of Astro Bot’s development, including five ways the game uses space to create what he calls ‘VR-ness’.

“Early on we realised that to establish the full potential of VR, you have to become the only way to operate the camera in the game,” says Doucet. “So we decided to continue not using the right thumb stick, and instead decided to look for fun ways to use your body. And that became the VR-ness.”

Aside from the self-proclaimed barbaric use of English, Doucet defines VR-ness an as ensemble of five gameplay facets that take advantage control and interaction within virtual spaces.

Perspective play

Perspective play, as Doucet terms it, is method of camera movement most unique to VR. Unsaddled by a traditional camera, a player can use their upper body to lean and look around objects. It has a speed and fidelity of movement that’s hard to recreate in using traditional video games controls and cameras.

“It complements platforming really well,” he says. “We’ve been using it at every opportunity in every level.”

In one example, a trail of coins provides the player with a hint that something is hidden behind a platform. This hidden object can only been seen by physically moving towards the obstruction, and then peering behind it.

“You can also use it as a way to surprise the user,” says Doucet. “You’re not seeing anything, and then the moment you lean, you can see two enemies.”

Vertical play

Creating a sense of scale and verticality is one of virtual reality’s biggest tricks, and it was something Asobi Studio used throughout the game.

“We made really heavy use of verticality throughout the levels. You often drop down, really far, to large play areas down below. The change of height is really powerful and we use bumpers as an effective way of quickly switching from the bottom to the top,” explains Doucet. “Then you can see gameplay from underneath. It is really dramatic to be able to control your character from this angle. At every opportunity we are looking for ways to verticalise the experience.”

Controlling a character from beneath is a new experience for most players, so special consideration was given to the objects Astro interacts with, and the location of the player.

“Sometimes you can get your view obstructed, especially when you are viewing Astro from underneath,” Doucet says. “So we developed platforms that you can see through, for example leaves, or glass material. Also platforms are always placed so that, according to your physical position, you can always catch a glimpse of your character.”

Near play

Playing with distance is also effective, and helps to create different emotional relationships between the player and Astro.

“We took every chance to create moments where Astro was nose-to-nose with you. For example, using ledges that stick out very close to your face.”

It one sequence – set underwater – the player can get so close to Astro that he can get stuck to your face. The aim is create an emotional connection.

Far play

The opposite is also true, and sometimes the game will deliberately create distance between the player and Astro.

“With far play we take Astro away from the player. These sections very much feel like a 2D platformer. With far play, platforming can become a little bit difficult,” Doucet says. “Sometimes you might drop down the back of a level, so we reduced the gameplay to 2D and with these constraints it worked. You really don’t notice the difference when you go from full 3D to 2D gameplay.”

The distance between the two can also enhance the emotional connection.

“People told us they really felt worried when Astro was getting away from them because they felt powerless to help him,” Doucet reveals. “We used that as an emotional trigger.”

360 play

Creating gameplay that happens around the player also seems like an obvious choice, given the flexibility of a virtual space, but these moments should be used sparingly, says Doucet.

“We prototyped a lot of them but in the end there’s only one left in the game. They do take advantage of VR fully, but they are physically quite demanding. It’s really good, but it largely depends on how flexible the player’s body is. It can become quite a tiresome experience. So we only kept one in the game.

The neck check

So how do you know if you are making a gameplay experience that takes full advantage of virtual reality? It’s quite simple, says Doucet: You do a neck check.

“One way to know if a game is using VR-ness, is to watch peoples necks. If they are not moving enough it means that we need to adjust the level, or stretch the play field to create more of these moments. “

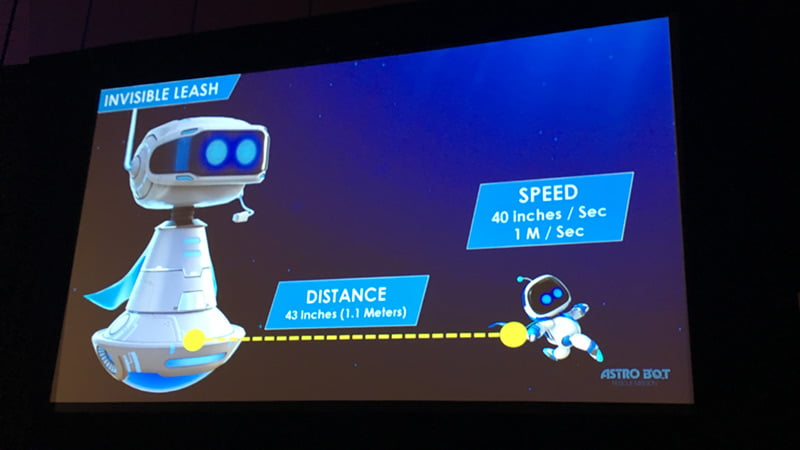

And to ensure that players didn’t experience any discomfort while playing Astro Bot Rescue Mission, particular attention was payed to the distance between the player and Astro. An invisible leash runs at a length of 1.1 meters between the two, and once Astro reaches the limit limit of the leash, the camera begins to follow at a speed of one meter per second.

“It feels strange at first because there’s no reference point, but over time in your brain you get this print of exactly where the invisible line is. And when you start moving, you know what to expect. The important part is to be consistent, so that distance and that speed will never change,” Doucet explains.

Despite the intricate and complex levels in the game, it’s also interesting to note that the player only ever moves on a fixed line.

“The levels are built to be twisting around you,” Doucet says. “But at the end of a level if you ask somebody how they felt the level went, they would tell you that they have gone up and down, left and right. In fact, your body has only gone in a straight line.”