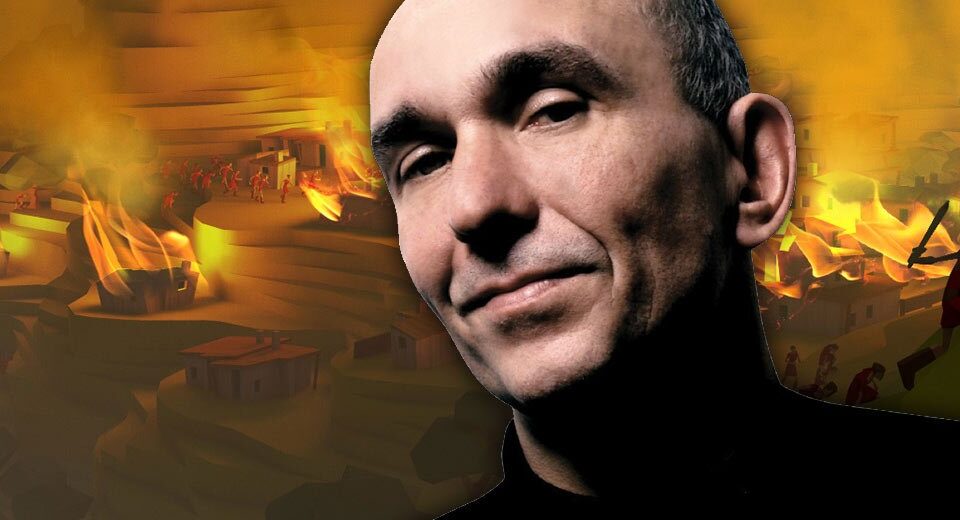

Highly regarded developer (or overhyped creator whose promises often do not come to fruition) Peter Molyneux recently gave an insightful interview with Rev3 Games in which the focus was on his current title, Godus.

Godus is a spiritual sequel Molyneux’s 1989 game, Populous, which is often considered the first “god” game. Continuing in the experimental approach of his new company, 22Cans, since leaving Lionhead Studios (which he founded) and Microsoft (where he was Creative Director of Microsoft Game Studios Europe) he decided to crowd fund the game via Kickstarter. However, the Kickstarter campaign only reached its £450,000 funding target two days before the campaign ended. Causing some doubt as to whether there was adequate demand for such a title.

Regardless of the campaign only just reaching its target, and whatever your opinion might be on Peter Molyneux, one still has to recognise his achievements. After all there is a reason why he has been recognised for his contribution in the industry by BAFTA, as well as receiving an OBE in the United Kingdom and awarded the title of Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France. Although he is not quite as prominent as he once was, in part due to being more hands-on role in his role on Godus, he still finds time to talk about the medium and explain its intricacies to those outside the industry.

It would appear that Molyneux has learnt from his previous games not to make bold announcements whilst they are still in development. Instead he has shifted towards how he envisions the future of the medium. This becomes evident in the Rev3 interview and it is one that can be seen as problematic.

After completing the Kickstarter Godus has since been released on Steam as an Early Access Game, which allows people to buy the game despite it still being in development. Therefore people are paying for an unfinished product and are contributing to the testing process. During the interview he spoke of how he has felt the need to constantly remind people that Godus is not a finished game and that people should not prejudge it whilst it is in this state.

He gives an analogy of building a kitchen during which his wife would remark that there was a part she did not like and that it should be changed, but only once it is finished she then says how good it is, including the part that previously she has not liked. This is true of most things, especially video games. The problem with this approach is that those playing the game in this stage will be very vocal about anything they feel is wrong with it, and sometimes accompanying those concerns with almost threatening demands. Following the analogy Molyneux stated that if you stick to a vision then the end result will be better, but not if you constantly listen to people about parts they do not like and then change things to appease this crowd.

So why has he chosen to go down a route that allows for such intimate exploration of a game before it is anywhere near completion? This approach is further put into question when he later states that the game might never truly be finished, as the day Godus is released will just be another day of development, therefore contradicting his previous analogy. Yet he feels that he is staying true to his vision and not allowing himself to be intimidated and bullied by the crowd. He even admits that as terrible as Early Access can be; it is something beautiful, and adds that in his opinion he thinks that it is the only way to make video games now.

The reasoning behind this is because he likes the feedback that it presents, he gives the example that some people played the (unfinished) game for 600 hours, which provides plenty of data. This feeds into his love of analytics, but he is not as interested in how many people play or even for how long (despite noting how long people have played it for), but rather what it is that they are doing whilst they play. It is this information that he finds more useful when deciding how to alter the game or what to test next.

Admittedly Godus is a game that can lend itself to being an Early Access Game due to its open nature and emphasis on player decision, similar in a sense to what made Minecraft so successful during its public alpha and beta stages, which helped to bring about the current environment that so many games are taking advantage of. Although in the case of Minecraft from very early on due to the focus on creation there was always sense of completion. It did not feel like one was playing an unfinished game, the parts that were added were just that, additions. Whilst they changed aspects of the game, the core was unchanged, and this allowed it to continue to gain new players, whilst also still keeping existing players happy.

The way in which 22Cans relies on those participating in the Early Access build appears akin to that of outsourcing what would primarily be the task of internal Quality Assurance (QA), who would test the game and highlight any problems or areas for improvement. Usually this would cost money, but with early access this cost is removed and instead replaced by willing paying participants. This does make sense for small studios, and in this aspect 22Cans is no different, but it is understandable why some people find it off-putting when someone like Molyneux asks for money via crowd funding even though he has personally invested his own money into 22Cans.

Molyneux is not immune to all criticism as he calls out a critique of Godus made by Eurogamer (likely that made by Tom Bramwell, although he does not mention him by name) which criticises the approach taken and states that there are aspects of the game that are unlikely to be fixed. Molyneux again talks of his frustration of having to repeatedly state that ‘it’s not a finished game’, but just because it is not finished does not mean that that is the cause of the concern. It could have been a concern about a core element of the game which is not something that can simply be fixed throughout the continuing development without intrusive reworking.

Towards the end of the interview Molyneux refers to the problem that was present with the previous games he worked on whilst at Lionhead Studios, this being the issue of length. Fable 2 took three years to make and Fable 3 took two years, yet he would find that there were people who would finish these games within a weekend, and that they had consumed all of the content that had taken years to create. This is not a problem, he claims, that will be present with Godus. Although the two are quite different games, so it is not surprising that length is not a main concern with Godus. But this does signify dissatisfaction from Molyneux towards video games with fixed narrative or predetermined endpoints in favour of more open ended experiences.

It is therefore not too surprising for Molyneux to make the statement that these days ‘you don’t finish [making] a game’ which is why when Godus is released it will just be another day of development. Yet just because it is his preference does not make it the future of video game development. Not all games fit this approach, and nor should they. This type of development does have a future, but it should not be the only way in which the medium moves forward. There will always be a place for games with a predetermined endpoint, but now there is also a chance to allow for continual experimentation, which increased connectivity is facilitating.

Godus is not just a game, for it is also Molyneux’s personal laboratory, but this is in keeping with 22Cans desire to experiment, as was evident with their previous “game” Curiosity. It is still unclear how successful Godus will be when it is finally released, but ultimately it is for Molyneux to decide whether this experiment has been successful or not whilst the rest of the medium continues to develop.