The winter and Christmas period has always been the time of year where a significant number of the big AAA games are released. Is that still the best model?

The winter period has always been the time of year where a significant number of the big AAA games are released. The rationale behind this is logical, it is the biggest spending period of the year, and with the medium being traditionally tied with the younger demographics of the market, Christmas is a time when little Billy and Millie can ask for a video game or two, or maybe even three.

This logic has become engrained into the strategies of the largest publishers and has seen them continue to focus on winter as the launch window for their major releases; the sort that determines the company’s results come the end of the financial year. However given that the majority of these releases are for more mature audiences (with an M rating in North America and 16-18 in the UK/EU), and an audience with its own disposable income, it makes less sense to group all of these games together. That, of course, does not exclude these video games from being given as gifts, nor does it negate parents buying the latest M rated Call of Duty for little Timmy.

However, with so many big AAA video games, of which there is often genre overlap, the crowded marketplace becomes overwhelmed. This overcrowding at the end of the year has ramifications for other parts of the year, resulting in the infamous annual “summer drought”, whereby the summer months are devoid of big releases. The irony of this is, going back to the previous point of younger demographics, that this is when consumers have more disposable income, especially in the U.S. This year has seen the ramifications of similar releases negatively affect sales figures, with Titanfall 2, Dishonored 2, and Watch Dogs 2 not just underperforming, but also selling less than their predecessors; by as much as 80% for Watch Dogs 2. This is not an example of sequel fatigue though – but might be with Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare – as Titanfall 2 and Watch Dogs 2 have both reviewed better (and Dishonored 2 coming pretty close) than their predecessors.

There are different potential reasons that these titles have performed worse at launch this time round. We are now three years (excluding the Wii U) into this console generation, and the original Titanfall and Watch Dogs were released in the early days of these new consoles when there were not as many games to choose from, and there was considerable hype around these titles demonstrating the transition to next-gen. Even though the install base would have been lower, if a greater proportion of that base (literally) buys into the hype, it makes a noticeable difference. The original Dishonored had the benefit of being a comparatively unique title coming out towards the end of an overly protracted console generation, whereas now its sequel comes out at a time where, in addition to many new releases, it is also competing with people’s backlogs.

This is another element that is potentially having a detrimental effect upon new video game releases, especially when they are bunched together at a single point in the year. This could be the midpoint of the generation (if we view the PS4 Pro and maybe even Microsoft’s Project Scorpio as mid-gen refreshes), which is when developers are by now familiar with the console architecture and a healthy install base exists. But with the rise in the number of smaller games on consoles, and the increase in length of AAA games, people are already struggling to get through their backlog; and this has only gotten worse with “free” games provided via PS Plus and Games with Gold.

When people already feel like they have enough video games available to them to play, it is more difficult to convince them to buy another, especially when they know it will most likely drop in price if they wait anyway. Unlike film, which is essentially split into two types of revenue streams, cinema release and home release, video games only have a home release, and the industry depends upon launch sales to recoup as much of the development and publicity costs as possible. Although film does depend on cinema releases and especially opening weekend despite having a second revenue stream, meaning that video games have not learnt from the unconstructive processes of the film industry.

What video game publishers potentially need to embrace (or at least try to incorporate into their forecasts) is the “long tail”, an economic theory put forward by Chris Anderson. This theory should complement video games given the significance of past titles upon the medium and the evolution of digital distribution. For the long tail focuses on the relevancy of sales either from more obscure titles (part of the reason why Amazon is successful as it has the space for more variation) or can be interpreted to mean the continued, albeit lower, sales of a video game long after its release. Many of Nintendo’s titles such as Pokémon and Mario Kart are examples of the long tail in action, for these titles continue to have healthy sales despite their age, even though they are no longer reaching the same numbers seen at launch. Nintendo can be seen to be actively embracing this with the recent update for Animal Crossing: New Leaf bringing the game back into the gaming consciousness and allowing Nintendo to give people a reason to buy more amiibo.

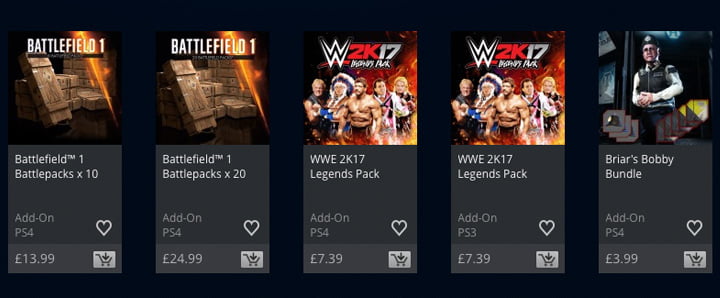

Digital distribution is complicating matters but also provides an opportunity to embrace the long tail. It reduces the problem that physical retailers experience of having old stock taking up shelf space, and trying to clear it to make space for the new. But the industry still has a fixation/dependency on physical sales and still uses them as the main basis for analysing sales, even though digital is continuing to become more prevalent. What’s more is that neither type of “full game” sales shows the whole picture, for the rise in DLC should not be overlooked as a continued source of additional income. Where physical sales are falling, digital sales are rising. Unfortunately, a direct comparison is surprisingly difficult to make, but what can be identified is that both Ubisoft and Activision, for example, have seen digital revenue grow by over 100 percent.

Publishers are aware of the advantages that the digital landscape provides, and the greater access they have directly with the gaming community. This can be seen with the amount of information they make available to gamers during E3, almost circumventing the video games press, resulting in a highly informed consumer base. In addition, the three AAA FPS games released this winter each had a public beta (as well as closed alphas/betas for EA’s games) bringing in active engagement from the public in the lead up to their release. These are for the purpose of stress testing the servers and checking for game balance, but they can also serve as marketing for the game, in effect an online demo. Combining the additional information output of E3 and the increased use of public beta’s further diminishes the importance of winter working as a marketing ploy.

Spacing out releases into “quiet” months has traditionally been seen as a risk, as they might be lost during this uneventful period of time. Although video games can be successful launching during these times, such as with the Mass Effect sequels which were released in January (2010) and March (2012) to notable success, with Mass Effect 3 launch sales in the US were double that of Mass Effect 2. This demonstrates that is it is possible for sequels to do well when launched outside of the winter launch window. However what that means for new IP and when is best to launch them is not as clear. But if one thinks back to the original Titanfall and Watch Dogs launches, their novelty might help them stand out.

Even if games do struggle during a winter launch, that needn’t mean the end for them. Ubisoft experienced disappointing sales with Rainbow Six: Siege, which released in December 2015. Ubisoft did not give up on the game and has continued to support it with extra maps being made available for free, and in-game purchases are only for character customisation. This has helped to keep the game relevant with an active player base, which is essential for online-based games. Ubisoft has acknowledged the benefits of this approach and has announced that there will be “no more DLC that gamers have to buy for the full experience”. This is still misleading, as what counts as a “full experience”? Does the extra DLC contained in the Watch Dogs 2 season pass not comprise as the “full experience”? Also, what about Tom Clancy’s The Division, should its expansions be free as well? What this seems to be doing is distinguishing between single player games and online multiplayer games that can be seen more as a service, and therefore with the latter, when it releases could be less reliant on winter and depend more on how to sustainably build up a player base.

Understandably, a lot does go into the decision process surrounding when a video game is released, and of course how close a game is to actually being in a playable state is still important for AAA games (compared with smaller games that experiment with early access). But content wise, how complete a game might be is less crucial than before. Small bugs can be fixed with a day one patch and other features can be added later, via a free update. For publishers getting the money now, and delivering the rest of the experience later, can be an appetising option. Unfortunately, this means that whereas a video game might have previously been pushed back until after Christmas, it will now be released anyway, because the publisher knows it can be fixed later; just look at Assassin’s Creed: Unity.

This has led to distrust from gamers, and with disposable income under increasing strain, the price of an AAA game is becoming more difficult to consider. Therefore the one game they do buy might end up being the more conservative choice, with the other options saved for the quieter months in the following year.