Math Manent’s Nintendo 64 Anthology arrives as Nintendo’s much loved – and much maligned – console celebrates its 20th Anniversary, but is it a worthy celebration or an opportunistic cash in?

Books dedicated to historicising video game hardware are nothing new. In recent years we’ve seen the publication of tomes celebrating and commemorating the ZX Spectrum, the Commodore 64 and the Sega Genesis, to name a few.

Each of these books has been a passion project created by, and for, dedicated fans of their respective subject matter. Some titles, such as the Sinclair ZX Spectrum Visual Compendium, are content to let the raw beauty of its system’s graphics take centre stage, accompanied only by a light commentary. With Nintendo 64 Anthology Math Manent has taken the opposite approach. He’s thrown in the kitchen sink, and then some; the result is the best book of its kind by some distance.

Nintendo 64 Anthology is split into five sections. The first covers the fascinating – and often troubled – development of the Nintendo 64 hardware. It’s a broad but well researched examination that covers the breakdown of Nintendo’s partnership with Sony, the decision to eschew CD-rom technology, the impact of the console’s ground-breaking games, and the Nintendo 64’s ongoing struggle to compete with the sales of the first PlayStation.

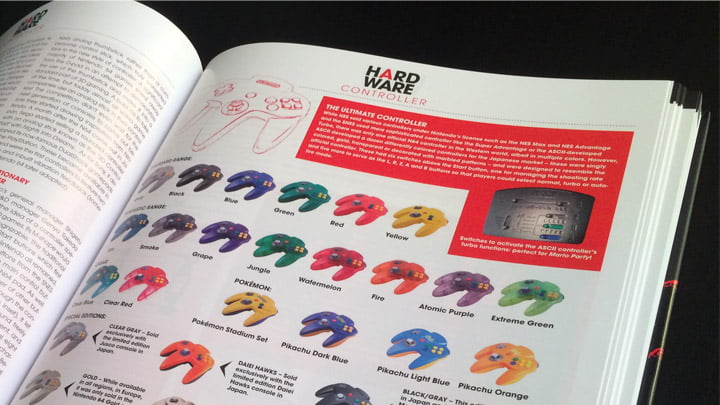

Elsewhere, the book looks in detail at the various iterations of the N64 hardware, and its extensive range of peripherals and accessories. Another chapter unearths many of the titles that were in development but never saw the light of day, and another highlight is a thorough look at the Nintendo 64’s oft-forgotten, China-only variant, the iQue.

The book also features comments from various developers who created games for the Nintendo 64. The most fascinating is an interview with GoldenEye 007 director, Martin Hollis. The ten page feature is illustrated with a stunning collection of sketches and design documents, and Hollis’ recollections are amusing, honest and insightful.

The bulk of the book chronicles every single game released for the Nintendo 64 around the world. Some of the more noteworthy titles receive a full-page of coverage or more, others just a column, but each entry contains a nugget of information about the development of the game, its release, reception, or impact. As an aide memoir, it’s exceptional, dredging up long-lost memories of classics like, erm, Armorines, Fighter’s Destiny and Rocket: Robot on Wheels, as well as digging deep with the likes of Super Mario 64 and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time.

Visually, the book is a delight to explore. Each of its 384 pages is studded with pictures of consoles, accessories, screenshots, box art, advertisements and magazine covers. The image selection alone would make the book an excellent visual compendium, but fortunately, the text is just as compelling.

Manent is enthusiastic, but not fawning, about the Nintendo 64. He’s as comfortable in criticising its shortcomings as he is in praising its achievements and impressive roster of first-party games. This gives Nintendo 64 Anthology an even-handed tone that is missing from other books with a similar intent. A surfeit of exclamation marks and the odd turn of phrase belies the book’s French language roots, but it’s a small niggle in an otherwise informative and thorough read. And given the number of basketball games released on the Nintendo 64 I can only commend Manent for keeping his commentary fresh and insightful as he works his way through jam after jam and jam.

If you were an Nintendo 64 owner who clung to hope that Turok 3 might be a classic, or that World Driver Championship would be a Gran Turismo killer, this book is an essential purchase. And even if the console didn’t play a huge part in your life, Nintendo 64 Anthology is a fascinating record of a revolutionary and experimental time in the history of video games.