Today Lego games are synonymous with highly successful film franchises such as Star Wars (which began this trend), Indiana Jones, Batman (and his fellow DC heroes), and the Marvel heroes. Despite the association with these franchises (technically making them tie-in games) they have been both hugely popular and also well regarded by critics and fans alike. The British based Traveller’s Tales found a formula that encompasses the flexibility of Lego bricks as well as staying faithful to the series it is depicting.

However this approach wasn’t always the case, whilst there are some games not based on film franchises, most of these are instead based on Lego franchises that also come with their own films and wider media presence. The only truly “original” title was Lego City Undercover which as the name suggests builds upon the Lego City construction range. Prior to the first Lego Star Wars game most of the games were original titles that incorporated different Lego sets to populate and diversify them.

Even though the early titles weren’t particularly unique in terms of their gameplay, the integration with the building concept that is central to Lego was enough to differentiate them from their contemporaries. Lego Racers was a fairly typical kart type racer, but it allowed the player to build their own vehicles to race, making it more akin to what they might have done when they were younger playing with the physical Lego cars that they created and pretended to race.

With Lego Island though the idea was to create a game that took the basic concept of what Lego is and provide an accessible experience for children to explore a digital environment within the confines of what technology allowed for at the time. Lego Island might not be a true open world game, but it offered players a level of freedom that was uncommon for the time and would continue to be so for years to come. Players were free to explore the island at their own pace and take up tasks in any order.

The tasks were very straightforward, some were simply to go from one place to another and then click on something, others allowed for different vehicles to be created following a set design (with the only real customisation being the choice of colour), and finally were the jet ski and Formula 1 races (which were unlocked after having built the vehicle).

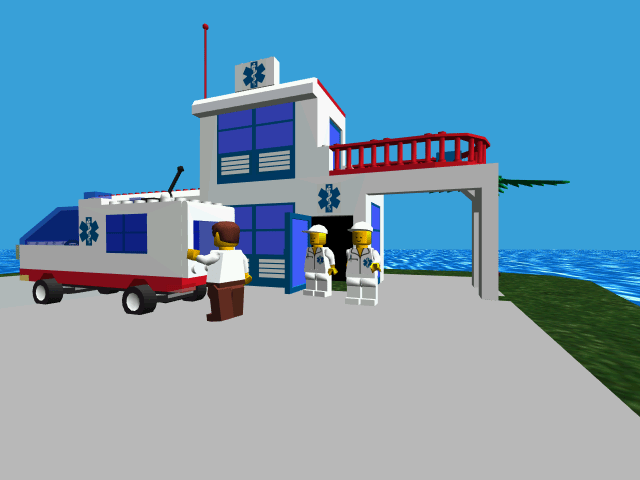

Despite the simplistic nature of the tasks, the circumstances around them were by no means ordinary. During the Paramedic task you are accompanied by Enter and Return who are two bumbling fools who have no right being involved in medical treatment. Then again this is Lego Island, where injuries can include swallowing a shark, which in turn has swallowed a dog, which swallowed a cat that finally coughs up a parrot. This all takes place outside the kitchen at the pizzeria, thankfully they don’t have to worry about health inspectors on Lego Island.

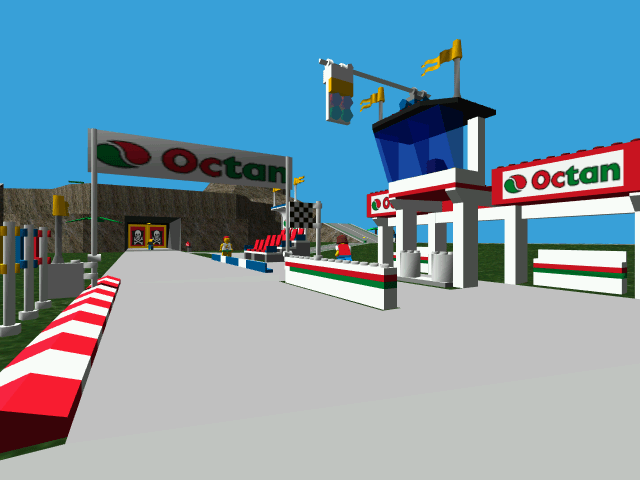

This is nothing though in comparison to the absurdity that one finds during the F1 race. Sure the starting line accompanied by the standard grandstand suggests all is fine, until you smash through the pirate doors and then into a large cavern filled with giant pizzas rolling around with skeletons riding atop them. It is here that the spirit of Lego really comes out in the game hidden under the superficial normalcy of the island. This is because as all of us will remember from our time with Lego as a child that ultimately pieces from different Lego sets will end up in the same box, so having a pirate alongside a modern race car no longer seems an unimaginable situation.

Whether this was intended or not but the use of the first person perspective also reinforces the focus on the player being the one interacting with this environment just like they would when playing with real Lego. Although this element is somewhat negated by the fact that in this entry players can rotate between playing as Policeman Nick Brick, Policewoman Laura Brick, pizza chef Papa Brickolini, piano player Mama Brickolini, and pizza deliverer Pepper Roni (who can be considered the main character and is the only playable character in the sequels). For the most part there are only subtle differences between the characters which are mostly in the dialogue that that they will use to address you with.

Talking of dialogue, the game is still amusing today because of it. To a certain extent this will depend on your tolerance towards the use of puns, with one notable offender being William, or as he refers to himself, Bill Ding (get it), who helps you construct the different vehicles. Nonetheless the range of characters all have distinctive characteristics regardless of how important they are for life on Lego Island, and the quality of the voice acting helps to overcome what at first glance would appear to be generic archetypal characters.

Pepper (the dude with the food who can also spin more degrees on his skateboard than are present on a thermometer) has an edge over the other playable characters due to the fact that his pizza delivery quest results in the escape of the despicable Brickster; Lego Island’s one and only criminal. With this criminal mastermind loose to take apart the island brick by brick it is up to Pepper to help facilitate his capture. It is during this task that the game can be “won” or “lost” as succeeding or failing the task results in the closest thing to an end state for the game. All this really equates to is a different cinematic and closing statement by the all-knowing Infomaniac, as the game reverts to normal regardless.

The interesting thing about the games “endstate” is how quickly it can be reached and then subsequently finished. If one thinks about it the time it takes to “finish” Lego Island is similar in length to that of Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes, a game that many criticised for being too short. Yet like Lego Island, Ground Zeros can be seen as a small playground which the player can explore at their own pace and then when they are ready can proceed to the end goal. For finishing the narrative in both games is not the end, nor the point of the game, exploration and experimentation are.

Part of the reason of Minecraft’s success is down to the fact that it presents players with what is essentially digital Lego and a world that they have total control over. Lego Island does not offer the same amount of freedom, but most of the non-geographical elements of the island adhere to the logic of actual Lego bricks (although not to the extent found in the Lego Movie, as technology has come a long way since) which added to the feel of the game, especially back when it was released in 1997. This also helps prevent the game from looking too dated, as the visual style of Lego bricks doesn’t age.

Unfortunately the same can’t be said for the controls, which were never great even for the time, but today help bring about a sense of nausea that one would potentially expect from VR rather than a game that is now old enough to legally drink (in the UK).

Lego Island is often remembered more due to a sense of nostalgia than for anything particularly memorable that it did. However it was in fact more revolutionary than people give it credit for. Whilst it might not have actively inspired the video games of today, one doesn’t have to look too hard to find games that share it sense of laid back exploration. Recent indie titles such as Proteus and Jazzpunk come to mind when considering the type of freedom but also the absurd sense of humour present.

It is not too difficult to find a copy of Lego Island, or maybe you have one buried away somewhere, but it is worth visiting the island just to meet the array of bizarre residents and soak up the surprisingly catchy tunes. It’s a change in tone to the current batch of Lego games, but one that focuses on the expressive nature of the core Lego series of bricks rather than the pre-designated franchise tie-ins present today.