The Order: 1886 never really stood a chance with critics, its existence marred with sourness from a gaming landscape frustrated with a lack of immediately immaculate games at the launch of this new generation of consoles.

Doubly against its luck was the context that The Order: 1886 was untested studio Ready at Dawn’s first original game, having previously only worked on defunct PSP games and ports for titles like Okami and God of War. Early winter 2015 marked the dawning of a ravenous environment starved of major, console-exclusive releases for the PS4 and Xbox One that would justify the purchase of such costly, seemingly unwarranted machines. It was a pre-Bloodborne world, and the rotten memory of the forcefully hyped, ultimately underwhelming blockbuster behemoths Watch Dogs and Destiny still lingered in the mind.

Thus, The Order: 1886 bore on its shoulders lofty goals that it could never and should never have had to reach. As a console exclusive and graphical wunderkind, the game appeared set to validate an entire console’s existence and launch the new generational zeitgeist like how the PS3 was supported after its first few months with exemplary, console-exclusive support from Resistance: Fall of Man and Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune.

Of course, these were demanding expectations—intentional or not—that no game should have to endure, and The Order undeservedly suffered for it. But for those of us willing to give unheralded games another chance, The Order: 1886 proves to be a genuinely fascinating genre offering both in terms of what it outwardly accomplishes and what it inherently values as a video game. I title this column “second shot” because I want to make a serious case to reevaluate games originally shafted by critics or given a lukewarm response by the community. When people advocate for the reconsideration of games, the discussion often leans on childhood nostalgia rather than thoughtful dialogue. Very rarely do people unpack the thematic, stylistic, or narrative thrust of these games with aplomb, and the “so bad it’s good” argument for some video games is really just lazy shorthand (the underappreciated and misunderstood Deadly Premonition is often a victim to this passive appraisal; this article calls such discussion into question).

This column, then, is a case for The Order: 1886 notwithstanding the contempt it garnered upon its release and its slippage out of sight from mainstream appreciation. I can’t name another game as meticulously visualized and concisely constructed as any recent genre exercise, especially considering the bloated and bland open-world action games (Mad Max, Far Cry 4) that have steadily oversaturated the market.

It starts in medias res with a flashback that will be reconciled after some hours of lush backstory and mystery intrigue. Ready at Dawn envisions industrial London with a finely detailed atmosphere like Charles Dickens by way of steampunk. The Knights of the Round Table are reimagined as a secretive, ancient order tasked with protecting society wherein members take on the monikers of the Arthurian legends. Mustachioed protagonist Sir Galahad joins Lady Igraine, Sir Perceval, and the Marquis de Lafayette in investigating and policing rebel activity around Whitechapel. Upon encountering werewolves—here called Lycans, from the Greek lykánthrōpos, or wolf-man—the Order prompts a more thorough investigation that unearths potential conspiracy and hierarchical shake-up within the Order itself.

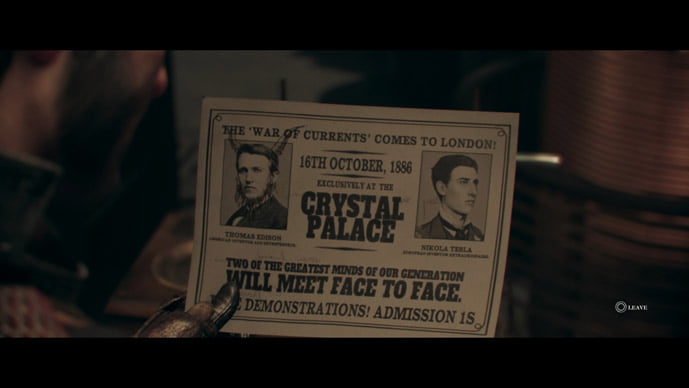

Galahad scowls and enunciates in a husky, sorrowful rasp that emulates the drab, pallid cityscape of industrialized London that you spend plenty of time leisurely touring. Following the opening flashback is a handsome panorama of the city that will eventually cede to claustrophobic interiors for most of the game, reinforcing its Gothic horror atmosphere and its themes concerning the chokehold of unchecked industrial expanse. Like the Assassin’s Creed series, The Order: 1886 mixes historical figures within its historical/alternate historical fiction including Nikola Tesla and Jack the Ripper. These figures inhabit an elegant if somber, lived-in world.

To simply inhabit the world of The Order is a pleasure in itself, adorned as it is with a smorgasbord of visual and literary influences that inform our gameplay experience. The aforesaid steampunk aesthetic shines through in the rustic weaponry and analogue gadgets encountered throughout the game. Its alternate history imagery fetishizes a synthesis of dirty, anachronistic Victorian apparatuses and luxurious aristocratic pomp. Walking through the lushly decorated Aux Belles Muses brothel, you’ll encounter candlelit interiors that set the frame awash in a shadowy sepia tone that contrasts the cold blue-grey lighting outdoors. The game’s painstaking work in populating these interiors with detailed props recalls the production design of Bioshock Infinite or Beyond: Two Souls, and even more vividly, it evokes the lush period cinematography of Steven Soderbergh’s television show The Knick. Pausing to absorb the scenery and take a look at the surrounding environment informs the world-building exposition, internal culture, and mood of the game. Elements like vintage advertisements, Victorian fashion, dusty photographs, handwritten stationery, dirtied mirrors, and faded Persian rugs contribute to the overall aesthetic and thematic experience. My personal favorite stylistic touch is the baroque Jules Verne influence in the form of a luxury zeppelin complete with hot air balloon escape pods. It’s a moment of playful reverence to a setting that’s completely outside of time.

The game’s conscious artistic choice to frame its action in a tight, letterboxed widescreen aspect ratio is a decision that should be analyzed on its own terms and not thoughtlessly spurned as meaningless. Like the fellow third-person action game The Evil Within, this cinematic widescreen presentation serves a thematic purpose, namely, to evoke a claustrophobic feeling of “closing in” on the characters onscreen. This makes particular sense in the survival horror gameplay and story of The Evil Within because it accentuates claustrophobic horror and visually cues us into feelings of anxiety. With The Order: 1886, the widescreen aspect ratio lends itself to the enveloping mise-en-scène of its interior locales. Sir Galahad has a sense that tension is brewing in the shadowy underground of Whitechapel, and the widescreen format narrows our vision to isolate him within the already tight, confining spaces of dingy alleyways and rickety hallways.

The carefully considered visual style that Ready at Dawn presents also reflects what kind of game it’s trying to be and what kind of gameplay experience it values. Even though The Order: 1886 is largely an action-oriented third-person shooter, it belies what we come to expect in this genre with atypical narrative choices: deceleration, elision, and above all, quiet downtime. Its generous moments of rest in between shootouts and other grandiose setpieces welcomes an enveloping stillness that urges players to consider environmental storytelling and atmosphere as fundamentally important to the overall gameplay experience.

The slow pacing as you unhurriedly walk through ornate spaces throughout London without much conventional (action-oriented) interactivity besides the basic act of moving and looking recalls the first or third-person walker strategies of works like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture or Journey. There’s something to be gained in linearity and the relaxation of gameplay in favor of video games’ most basic mechanics. When The Order: 1886 opens up possibility for peaceful downtime, it foregrounds environmental storytelling and atmosphere over combat.

As I’ve said before, The Order makes use of its sumptuous production design to define the look, backstory, and mood of the game. Consequently, the game shares more kinship with works like Heavy Rain or Life is Strange than your average third-person shooter like Mass Effect because it relies heavily on narrative cues embedded in the environment. These minimalist visual cues to interact with the environment permit the player to inspect items like photographs or advertisements and turn them over in one’s hand. Even if these encountered objects don’t service the main narrative, these moments communicate to the player the inquisitive and curious personality of Sir Galahad in investigative mode.

Indeed, The Order: 1886 is not worried in letting itself slow down to breathe and yet complaints of a boring lack of interactivity is often tossed around to disparage the game. Ready at Dawn is clearly highlighting a different kind of video game experience and sensibility in which mood and time is more critical than action-oriented gameplay. What most gamers see as pointless, slow excess is in fact crucial to what The Order is trying to accomplish.

The closest critical examination I can find defending this point is from Jake Muncy writing for Playboy, and he identifies the post-tutorial sequence of the game as a kind of unhurried morning commute and an establishment of “a narrative of place.” Although Muncy ultimately gives The Order a negative outlook overall, he at least notices its restraint when taken as an action-oriented genre affair in contrast with more breathless works. I’m more keen on applauding The Order: 1886’s willingness to decenter the story and linger on spaces and everyday moments seemingly inconsequential to the main narrative thrust. These aren’t superfluous experiences but real occurrences that comprise this world, and therefore it’s worthy of our time.

Even in spite of these quieter moments, The Order: 1886 isn’t without its share of propulsive, full-blown spectacle. Its bravura setpiece aboard a massive dirigible airship high above London provides a moment of breathtaking, panoramic catharsis after the first few hours traversing the game’s tight interiors and dimly lit underground spaces in tight widescreen framing. Here, the widescreen format suddenly works toward expanding one’s view rather than thematically constricting it. Quick shootouts and explosive reversals give way to open-air spectacle, and there’s plenty of excitement to be gleaned from such sequences.

These snappy skirmishes peppered throughout the game are contextualized within the Order’s larger objective in quelling an underground rebellion. As the game progresses, the werewolf conceit falls by the wayside to draw players into a deeper narrative with more weighty and consequential antagonists very much in line with its Dickensian inspirations. These themes revolve around the unchecked capitalist expansion of the fictionalized East India Company, here the United India Company, as a means to critique exploitative capitalism in the wake of globalization. There are shades of Bioshock Infinite in its brewing class rebellion, but The Order: 1886 is more refreshingly progressive in its critique of capitalism and not weighed down by casually racist narrativizing.

Two important women of color become major figures in The Order: 1886—Lakshmi Bai and Devi Nayar—and reframe the story from a different perspective. Lakshmi is the one who reveals to Sir Galahad the central conspiracy at the heart of the game, indicting the United India Company for systemically corrupting the government and military in order to police society from a safe distance. The real-life English East India Company was in many ways one of the first big globalized corporations, and its exploitative Company rule in India is called into question here by Lakshmi’s anecdotes. She is later revealed to be the real-life warrior queen Rani of Jhansi, a crucial figure in India’s war for independence against the oppressive British Raj and a historical symbol of colonial resistance.

What’s so refreshing about The Order is that the game sides with Lakshmi and Devi’s resistance movement and gives them agency and space outside the goals of Sir Galahad. Contrast this narrative decision with the casually racist undertones of Bioshock Infinite’s similar class rebellion tale. Bioshock Infinite introduces resistance leader Daisy Fitzroy and initially sympathizes with her reasonable grievances against the rampant racism of the caricatured version of Americana in which she lives. Later in her story arc, Daisy Fitzroy and her class struggle is unexpectedly and woefully demonized as stark raving mad for no discernible purpose other than for cheap dramatic twists. It asks of the player to disregard all initial sympathy for the racially-charged class struggle even when Daisy’s story was by far the most compelling element of Columbia’s twisted world. In The Order: 1886, women of color are not only treated with deeper consideration but are never exploited for such abrupt dramatics.

That The Order: 1886 allows the player to be part of Lakshmi and Devi’s class rebellion and sympathizes with it to the end is a rare accomplishment for gender inclusivity not just in video games but also in all forms of media. Very rarely do big-budget video games engage in progressive politics led by women of color (!) so confidently, allowing real-world themes to mesh with popcorn spectacle. The Order portrays the United India Company as a kind of allegorical, vampiric capitalism ready to pounce upon a young America, evoking related historical parallels like the nefarious Tammany Hall political machine or the industrial woes outlined in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. Ready at Dawn suggests that this era of capitalist expanse paved the way for globalized exploitation, creating rampant powers with no limits to geographical borders or political checks and balances. Not only that, but The Order: 1886 thematizes these ideas within an accessible, entertaining monster-hunting thriller.

In embracing atypical video game values like reticence, progressive politics, cinematic production design, and slow traversal over straightforward action gameplay, The Order: 1886 feels exhilaratingly new. Reactionary gamers have balked to such artistic choices, but it makes for a much more compelling experience than just nine hours of hollow squall. To distrust a game simply because its developers have embraced a “cinematic” style as though it’s a bad word is to ignore the grander cultural exchange that occurs in all arts. Video games don’t exist in an isolated vacuum, and it’s perfectly fine for games to engage in the sensibilities of other mediums to experiment with unfamiliar means of expression. After all, I found myself more engrossed in the tightly authored, linear narrative of The Order than the formulaic open worlds of Ubisoft games, and I enjoyed its nice respite from the tyranny of player choice. The Order: 1886 is a strange, wonderful alchemy. It has a willingness to instill authored choices such as guiding the player’s gaze towards evocative visuals worth looking at and directing the player’s emotions while leaving room for meaningful interactivity.

There’s a peculiar moment early in the game after the first Round Table gathering of the Order. A number of knights depart from the room after the session while others linger to huddle around and gossip. Sir Galahad rises from his seat and though the way out is right next to him, three other knights in deep conversation stand in the way. The game provides no choice but to laboriously traverse the entire circumference of the table to reach the exit just a few feet from where you once stood. It’s a perfect visualization of what I mean when reconsidering games on their own terms and to give such moments a second shot. While most impatient gamers would rebuke the hindrance as an irritating design choice, I can’t help but notice the somberness of the space and the pale shafts of light that cascade down from up high as I slowly make my way around.

There’s nothing really going on here, and it’s beautiful.