Arcade-to-home conversions in the 1980s often left a lot to be desired. Especially if you were gaming on the humble ZX Spectrum.

While the arcade games of that era were a riot of beautiful sprites, colour, and sound, the home computer experience was… different. The graphics were simpler, the colours clashed, and the audio was usually a series of sad beeps trying their best to resemble music or sound effects.

My favourite arcade game in the late 1980s was Double Dragon. Not necessarily because it was the best – although it is now considered a classic – but because it was the first arcade machine I could claim to know inside out. I had a firm grasp of level layouts, enemy types, and combat intricacies. Tucked away in an east London working men’s club, my friend Adam and I spent happy Sunday afternoons dealing out flying kicks and baseball-bat hits. There was nothing we enjoyed more than stepping into the shoes of Billy and Jimmy Lee while our parents stood at the bar, sipping gin and tonics and putting the world to rights.

Arcade conversions to home computers were common, and I owned a number of ZX Spectrum ports, including Paperboy, Renegade, and OutRun. I was perfectly happy with their quality, as I only knew the arcade originals by reputation. The cuts and concessions made to get them running on Sinclair’s modestly powered home system were mostly lost on me.

So when Double Dragon came to the ZX Spectrum, I was all in. Here was a game I knew, loved, and couldn’t wait to play at home. I remember going to WHSmith in Romford town centre to buy it. I recall getting the bus back, poring over the oversized cardboard box and its glorious artwork. Then came the long wait, as the game slowly loaded from cassette, accompanied by the usual cacophony of screeches and whines.

And then, all too clearly, I remember the crushing sense of disappointment when the action began, because the game was terrible.

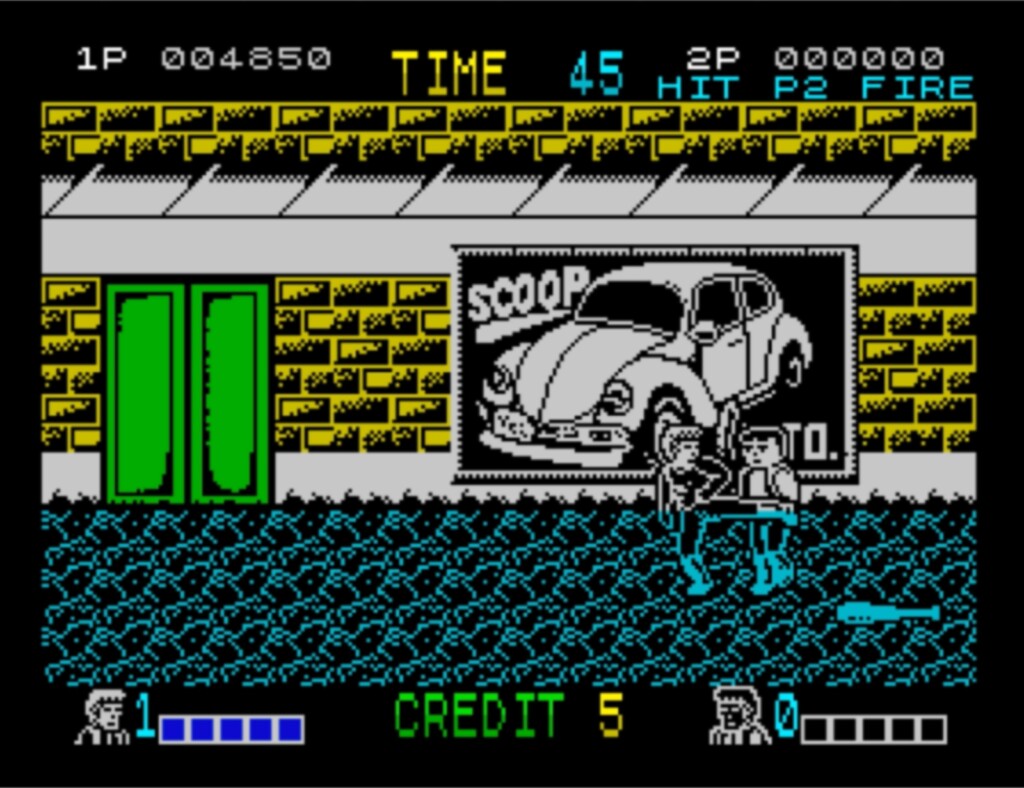

Action was too kind a descriptor. The port – developed by Binary Design and published by Melbourne House – was a sluggish, barely recognisable version of the game I loved. The graphics were reasonably detailed, but it was hard to distinguish between characters as they bunched together against the garish block-coloured backgrounds. The controls were muddy, and the high-tempo thrills of the arcade original were slowed to a crawl. It was, by all accounts, a bit of a disaster.

Still, I persevered, as one had to back then, and while I didn’t grow to love the ZX Spectrum version of Double Dragon, I did manage to wring some enjoyment from it. It wasn’t a patch on the arcade game I adored, but it was an echo, a rough sketch of perfection. And that was just about enough.

But the real impact of Double Dragon on the ZX Spectrum had nothing to do with how it played. This conversion was important because it was instrumental in shaping how I understood games and how they were made. It was my first tangible experience with the concept that games could move across platforms, and that the same title could feel completely different depending on where and how you played it.

Another example was Ocean’s port of Operation Wolf. I loved the arcade original and received the home conversion as part of a bundle with the ZX Spectrum’s Magnum Light Phaser. It was a much better effort than Double Dragon, but one still understandably constrained by the hardware’s capabilities.

Despite the shortcomings, these conversions fired my imagination. They got me thinking about the gaps between what I saw in the arcade and what I played at home. I started noticing how different systems handled graphics, sound, and controls. I became interested in the constraints of technology, and the creative ways developers squeezed magic from limited hardware. I began to appreciate games not just as experiences, but as interpretations. Ports and conversions, for all their flaws, were an education.

Nearly 40 years later, I still consider the same factors. Not in relation to arcade games anymore, but in how games scale across platforms. Is it possible that a Nintendo Switch 2 port of Star Wars Outlaws could be any good? Yes, absolutely. Can Baldur’s Gate 3 really scale down to be fully playable on Steam Deck? Of course it can. Mostly.

A game like the impressive-but-blurry Nintendo Switch port of The Witcher III: Wild Hunt is today’s equivalent of Double Dragon on the ZX Spectrum. Even though graphics purists may scoff at the compromises, that version will be someone’s first open-world RPG, and it will be just as important to their understanding of the complexities and magic of game development as Double Dragon was to mine.

There’s a danger that nostalgia makes everything seem better than it really was. My Double Dragon memories are certainly not rose-tinted, but they are formative. The port was flawed, compromised, and a bit of a shambles, and yet it still mattered. It revealed something bigger. Games aren’t singular objects like films or books. They’re shaped by the machines that run them, the hands and controllers used to play them, and the ingenuity required to make them work at all.

I can now play the arcade version of Double Dragon on Switch in all its glory, but it was the creaky ZX Spectrum port that had the biggest impact. It taught me that games are not perfect objects, but small miracles of compromise.