So, after GoldenEye and Metroid Prime Remastered comes Resident Evil 4.

The first was an unadulterated re-release, the second applied a layer of plush upholstery to the bones of its predecessor, and the third is a complete remake. But all three pay homage to the past, and to Nintendo, whose consoles first delivered them. In the case of the latter, it wasn’t long before the developer, Capcom, ported it to the PlayStation 2 – from whence it spread, like a dark infection, to every other platform on the planet. It’s impossible to believe that eighteen years have elapsed since its debut, on the GameCube, in part because of how fresh it still feels. One change, in the new version, is the scrapping of quick-time events, but the whole game is a quick-time event: closing the chasm of years, pinning your focus to the present, and pressing buttons to test your reactions.

Other changes wrought by the remake include, but are not limited to, Luis, who has a heftier presence and a beefed-up backstory; Salazar, the napoleonic creep with the powder-white curls, who is now a dead ringer for Margaret Thatcher; and your trusty knife, with which you can now parry attacks. Try it on one of those chainsaw-lunging brutes, and – in one of the least plausible and most winning sights in games this year – you will lock blades, amid a downpour of sparks, and impel him backwards. It’s a great piece of theatre, and a perfect summation of our hero, Leon S. Kennedy, a man of revved-up willpower and unleaded morals, willing to put on hold the laws of physics in the name of sheer style.

The role (or at least the likeness) of Leon goes to Eduard Badaluta, and you can see the thinking. For an operative of the United States Special Forces, Leon always looked curiously delicate, with his alabaster complexion and his chestnut hair, combed into a creamy part. He looked as though he would be far more comfortable on a catwalk, swathed in Burberry knitwear, than up to his shins in the dung of rural Europe. So Capcom has gone for the real thing: Badaluta is a model, who has, indeed, walked the walk for Burberry, and he brings to Resident Evil 4 (as he did to the remake of Resident Evil 2) not just autumnal beauty but a light mystery. You wonder about Leon, about what makes him tick and why he should prove so capable in the face of such overwhelming odds. If you have already conquered Instagram, I suppose, then the backwoods of Spain hold little threat. What’s he going to do, die of exposure?

The plot is as it always was. Six years after the events of Resident Evil 2, Leon – tuned and stropped by a classified government programme – has been asked to aid the president, whose daughter has been stolen. She was spotted in Spain, and Leon is dispatched, like a gundog, to go and sniff around. The kidnappers are Los Illuminados, a cult that worships a parasite, known as Las Plagas. We all need a hobby. This thing – basically, an enormous beige spider – likes to lodge in your body, snuggling up to your central nervous system and relieving you of the burdens of thought, free will, and, when times are particularly trying, your head. The remake preserves the grisly spectacle of the exposed Plaga: bursting from the neck of its victim and lashing the air like a nest of snakes.

“The solution, apparently, is to hold up the old game as a kind of icon, and the result feels like Warhol.”

What Capcom cannot hope to preserve, however, is the spectacle that grew out from Resident Evil 4. Horror games, action games, third-person games, Resident Evil games, and just plain video games were never the same again. The strategy of its original director, Shinji Mikami, was to take stock of the advice, often prescribed to writers, to “kill your darlings,” and to defy it. More than that, to muster an army of unkillable darlings and thus to forge a new standard. Ideas and flourishes that other games would make a meal of were treated like cigarettes – burned through casually, to impart a buzz, and flicked away without a care. Every ten minutes threw up something you had never seen: a chairlift set piece, with foes ferried your way, like a mid-air shooting gallery; a truck barging toward you, as you try desperately to snipe the driver; a chase through a string of suspended cages, each of which you detach, like train carriages, hoping to drop your pursuer into the abyss.

All three of these sequences have been cut from the new game, presumably to tighten the pace and tap into the grave mood of Capcom’s other recent remakes. Resident Evil 2 and Resident Evil 3 both took after their principal villains and harried you from start to finish; they bowed to the tyrant of our modern taste for the weighty, and reaching the credits felt like coming up for air. Mikami, on the other hand, was willing to swerve toward the comic and the camp, secure in the knowledge that his horrors would wind you in unease and whip you through the changes of mood.

That certain passages of the old game have been excised isn’t a problem, though zealous fans will doubtless mourn the loss of their favourite missing moments. The flaw of the remake is that it doesn’t replace them with wild invention; it planes and refines for the sake of keeping atmosphere and tempo – certainly no crime, in itself – and where it does make additions is to story and character. On the debit side, we have Ashley Graham, the First Daughter, also referred to, in radio communications, as “Baby Eagle.” In the original, Ashley was scarcely more than a yelper, her character barely hatched, who had to be plucked from harm’s way on a regular basis. Now she is a more solid presence. She is still in need of Leon’s protection, but she gives as good as she gets, even saving him once or twice.

We also have Luis, whom we find guilt-plagued over his past (he was an employee of Umbrella Pharmaceuticals, which has presided gloomily over the series since its inception) and his role in the present mess. He worked for Los Illuminados, helping to hone the Plaga into an even more deadly weapon. “I don’t want anyone else to get hurt,” he says to Leon. “In that case, you better get serious,” Leon says. Not so! Rather than mope about, or march doggedly toward his fate, Luis provides a welcome kick of comedy. At one point, he invokes Don Quixote, dubbing Leon his Sancho Panza, and he wakes the game up, reminding us how important humour was to Resident Evil 4, more than any other in its series. It’s an armour, to be well buffed and worn lightly, so that real grimness bounces off. Back in 2005, we saw Luis impaled on a scorpion-like appendage, belonging to the main villain, and cast aside; now he gets a knife in the back, and it suits him. His gallant mission to meet the world with a smirk has been betrayed by a narrative in thrall to the weighty. He didn’t get serious, and he got hurt for it.

As intriguing as these additions are, one question we might ask is: are story and character what we truly prized about Resident Evil 4? In a way, you have to feel for Capcom, given that conjuring an industry-shaking masterpiece isn’t something any developer can account for. The solution, apparently, is to hold up the old game as a kind of icon, and the result feels like Warhol. Hence the option, in the graphics menu, for enhanced “Hair Strands.” Leon, it goes without saying, is worth it, but it’s tough to shake the air of the sacerdotal. His hair, like his shearling leather jacket, have become relics of worship, and Capcom, as if tending to a cultish flock, has illuminated them afresh.

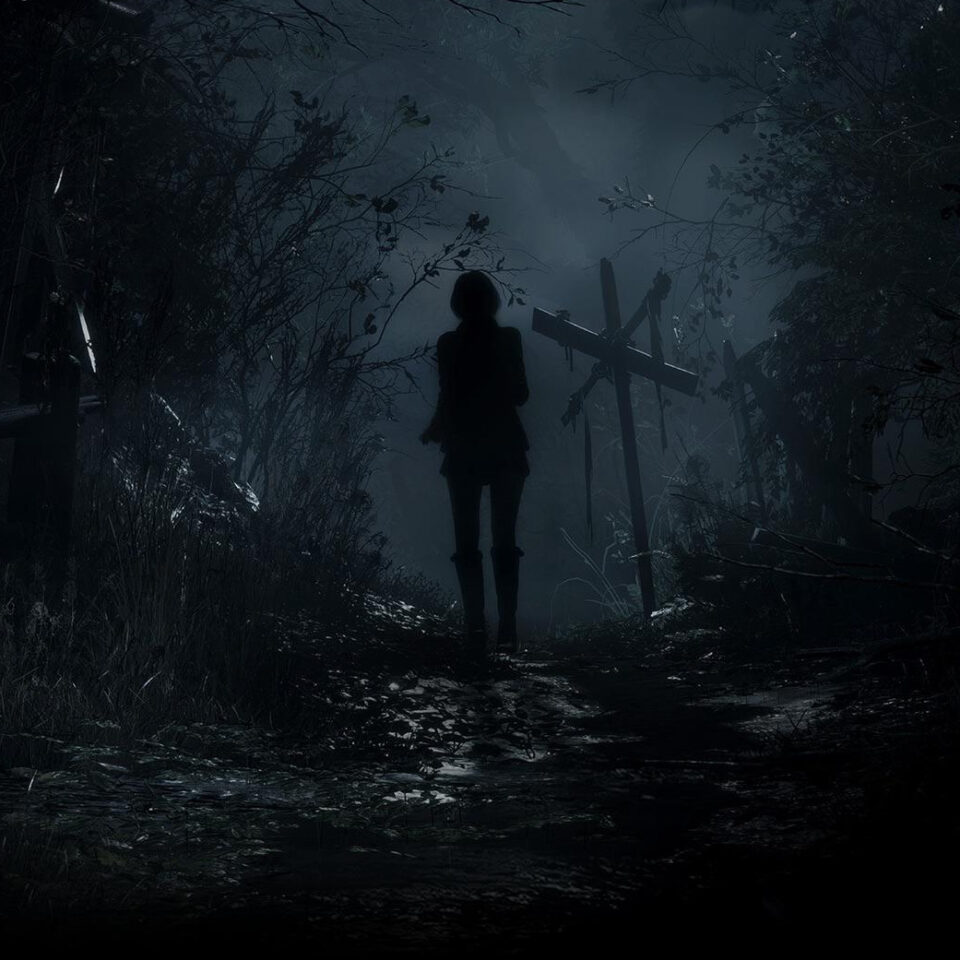

Still, there are consolations to be had. The first is one of basic shape. There simply aren’t many studios capable and willing to deliver a blockbuster, single-player, third-person shooter, and any effort to redress that balance is to be commended. The second is the RE Engine, which continues to be one of the most striking in the world. Here, it is turned equally to hair and trigger; the guns are lathered in rich detail and given luxurious closeups, with a fetishistic gleam. If that makes you a little queasy, look to the environments, achingly lit and rendered, which ravish the eye; check out the toasted glow that bathes a dying afternoon, early on. Personally, I still prefer the look of the original; there remains something rusted and perfect in its chronic preference for brown.

And so to the strange feeling that arises as you reach the credits. What next? Has the company’s remake crusade petered out, or reached its logical end point? The previous two re-imaginings looked to PlayStation games, and the reconstructions were dramatic, summoning not only graphical wealth but a change in camera and direction. With Resident Evil 4, that camera, along with so much else, was already in place, and there is a faint feeling of redundancy here. Is it blasphemy to wish for something new done in this style? If not, then I guess it’s full speed ahead to Resident Evil 5, a game made famous for its laughable excess, in which the hero proved his machismo by punching a boulder. Are the developers at Capcom ready for such a challenge? They better get serious.