Asymmetric Publications’ Zack Johnson speaks about jokes, the relationship between the player and the narrator, and more jokes in West of Loathing.

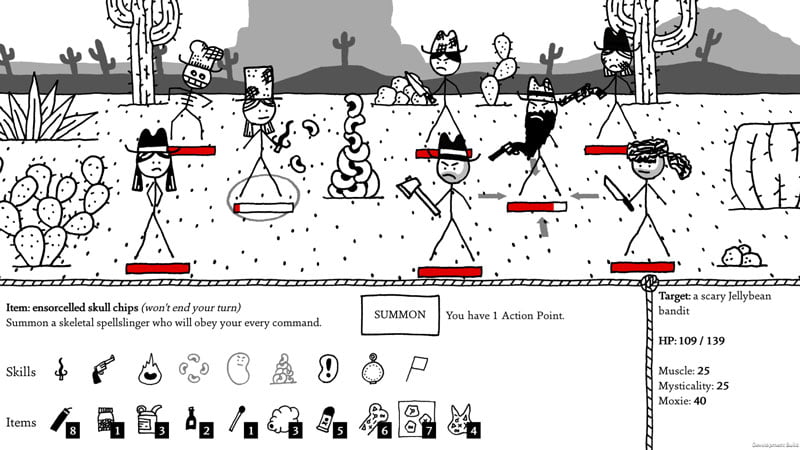

Slap-stick cowboy RPG, West of Loathing, is a spin-off from the long-running browser RPG, Kingdom of Loathing. Released on PC last year, it was an instant hit, growing a fervent fanbase that revelled in the game’s oddball sense of humour, and relentless jokes. It will no doubt find even more fans when it arrives later this year as a console exclusive on the Nintendo Switch,

In his talk at GDC 2018, Asymmetric’s creative director, Zack Johnson, spoke about the studio’s overall approach to comedy, and the importance of jokes in West of Loathing.

He began his talk by citing the following tweet from Double Fine’s Tim Schafer.

Comedy writing tip: When you’re writing something, don’t forget to put some jokes in there.

— TimOfLegend (@TimOfLegend) February 7, 2018

These words, says Johnson, hold the secret to adding humour and jokes to video games, and West of Loathing, at its core, is a video game made out of jokes.

“We decided when we started making the game that it was going to be a comedy game,” he says. “It wasn’t going to be an adventure game, or an RPG with comedy elements. Instead of a game with jokes in it, which happens all the time, this was a game made out of jokes.”

Despite this emphasis, West of Loathing needed some semblance of structure. To achieve this Asymmetric focused much of the game on the relationship between the player and the narrator.

“We wanted the player character to just be a cipher or an avatar of the player,” Johnson says.

The narrator, meanwhile, is a character in its own right, and a deliberate combination of both Johnson, and Riff Conner, the game’s other writer.

“What’s cool about that is that it allows us to treat the narrator as a character,” explains Johnson. “And because we’ve been doing this for so long, it’s a character that we’ve been developing for 15 years.”

“Having the entirety of the non-spoken text in the game be a dialogue between us and the player/character has a lot of advantages in us being able to cram jokes into literally everywhere. Every piece of text becomes an opportunity for us to at least try to be funny.”

This even extends to the game’s options menu, which famously features a a toggle for a colour blind mode.

“It’s a real quantity over quality approach,” Johnson says. “But it works because if you have a game with four jokes in it, and one of those is bad, your game is only 75% funny. However, if you have a game with a thousand jokes in it, and two-hundred and fifty of them are bad, then your game is 75% funny.”

Because the narrator acts as an honest reflection of the game’s writers, the conceit helped them overcome some of the game’s flaws by being self-deprecating, and acting like they were there on purpose.

“Because of the way the game looks, people come in with a set of expectations that are not ‘this is going to be an amazing, sweeping epic thing,’” Johnson says. “It’s okay to be a little goofy about it, because it is a little goofy. It’s not about being the biggest video game, it’s about sitting around with us, and having a fun conversation.”

This also means the player acts as the straight man, a foil for the narrator. It’s the tension in this relationship that creates much of West of Loathing’s humour, Johnson says.

“For the most part the entire game takes place in this jokey buddy cop conversation between the narrator and the character. Just being the default means of exposition for what’s happening in the game becomes an opportunity for comedy.”

It also allows the game to occasionally – and unobtrusively – break the fourth wall. Johnson explains using an example from the end of the game.

“At the end, once you finished the main storyline, you quit the game to get the ending cut scene, and it tells you this is not going to change things about your character, or the state of the world. You can just watch this cut scene, and you can leave and do something else, and then come back again.”

It was a method of letting the player know something genuinely useful about the end-game that was also consistent with the overall gameplay experience.

One major difference between West of Loathing and its predecessor is the volume of animation and movement, most obviously in combat. Because it’s a more traditional game in many respects, there was a concern that there wouldn’t be enough opportunity to write funny content. Nonetheless, Johnson avoided the temptation to add in walls of text, or significant blocks of exposition.

“I’m really glad that we didn’t do that. Instead we found other little cracks to put jokes in,” he says. “And I don’t think anybody it going to criticise West of Loathing for not having enough writing in it.”

Due to its design, the gameplay rewards for the player are, well, more jokes. The challenge for Johnson and the Asymmetric team was to ensure that any gameplay systems didn’t get the way of a humorous payoff.

“We kind of wanted the game to not be particularly hard,” he says. “We added an optional hard mode, just in case, but we needed to stick to the core. This game is made of jokes, and so we didn’t want to do adventure game puzzles.”

However, despite the team’s best efforts, it did become an adventure game, of sorts. One solution to mitgate this was to avoid obtuse puzzle design.

“We decided that if there was a puzzle that required a needle as its solution, we don’t want the player to live in a world where there is only one needle, and if you can’t find it, you can’t get past the puzzle. So we just decided to put a needle in every haystack.”

That’s game design, right there.

Although West of Loathing was extremely well-received by the majority of players and reviewers, its combat system was singled out for criticism.

“It is definitely the weakest part of the game,” Johnson admits. “And we all know this. And if we didn’t know it, a bunch of reviews told us.”

“The system is great and flexible and is capable of doing a lot of cool stuff, but we ran out of time and money. We decided that given that there’s not a way to make combat super-funny, and we don’t have time to make it super-satisfying, let’s just make it really easy.”

Despite the criticism, Johnson believes that this approach helped to serve the overall goal of making West of Loathing a game about jokes.

Where effort was spent, however, was on the large number of NPCs, and their dialogue. Riff Conner would visualise each one in a number of ways to ensure they were unique, be it in their appearance, their tone of voice, or their personality traits. And there was a fine balance to achieve in making sure the player would tolerate an NPC’s idiosyncrasies.

“Do they have an accent? Do they drops Hs, or clip Gs at the end of words? Do they say umm, or ah, or err? And how much of that can we put in the game before it becomes annoying to read? Does it even work in text?” says Johnson.

The type of humour was also important. Particularly the decision to avoid topical content – which dates blisteringly fast – or jokes that poked fun at religion, race, or anything else a player had no control over.

“You just shouldn’t be mean,” Johnson says. “The tone that we established with Kingdom of Loathing was that we didn’t ever want to make fun of anything that somebody didn’t choose.”

The same goes for politics. Johnson says that West of Loathing subtly says “the right stuff” rather than “the wrong stuff”, but it avoids aggressively aligning itself too strongly with any particular viewpoint.

“This is a very cowardly approach to politics, and I just have to own that!” he concludes.