We investigate the nature of an irrational childhood fear.

Fear is an ordinary part of our everyday lives. We all have fears—some mild, some severe—that we’ve had to learn to cope with as we live and grow. Me, I used to be terrified of insects—not of being bitten, not of being stung, but the buzzing sound that they made. I can’t help but feel like this had something to do with me growing up as an indoorsy kid, and in turn, developing a love for video games.

Fear isn’t always rational. I can’t remember just how many times people tried to cure me of my entomophobia with words. “It isn’t going to kill you.” “It doesn’t want to sting you.” It’s more afraid of you than you are of it.” None of that mattered. My brain understood that there was no real danger, but each time I heard the buzzing of insect wings, my body spun into a tense panic. I’ve overcome this fear with age, but I can still remember just how debilitating my childhood fears could be, and how far they reached.

For example, I didn’t beat Ocarina of Time until 2010 for one specific reason: I was scared of the Lost Woods. That statement usually gets me the same confused reactions: “The Lost Woods isn’t scary! And even if it was, how do you get scared of a video game?” I guess the same way you get scared watching a movie, or riding a roller coaster that’s been tested and certified to be safe—through immersion. Someone can explain to you all day that you’re in no real danger, but the body doesn’t care what the brain understands.

So far, my “Lost Woods” fear has proven to be pretty specific to me. I have yet to meet anyone else who avoided that place quite like I did. I have, however, made friends with several people over the years who share a different fear of mine—one that is unexpectedly prevalent in the circles I frequent: the fear of water levels in video games.

To some, this too might be confusing. “Water levels aren’t really scary. They just suck.” And that’s true; water levels in games have been notoriously bad (at least when I was growing up), but aren’t necessarily known for being frightening. And yet it is a recurring conversation topic among my friends and acquaintances, eager to share stories of the levels that filled them with dread, the games they couldn’t beat, as though we had all seen the same ghost hitchhiker. I’ve pondered these conversations off-and-on over the years, determined to find the connection between us. Which traumatic experience had we shared? Which video game left us all so uniquely scarred?

I was six years old when I played Donkey Kong Country for the first time. Back then, I didn’t really understand how video games were meant to be played. My stepfather would constantly remind me to move my character right—to move forward—but I didn’t want to. I wanted to explore. And so at the beginning of each session of Donkey Kong I would always retreat back into the treehouse, bounce on the tire for a while, go downstairs into the empty banana horde, and repeat the process, wasting a good five minutes before progressing into the game. For whatever reason, I didn’t like the game telling me what to do or where to go. I needed to be free.

And so, Coral Capers was like a nightmare for me.

Coral Capers

In hindsight, Coral Capers looks like a pretty straightforward stage. The music is calm and ambient. The level is simple and linear. There isn’t even a breath timer; you’re free to navigate the stage at your own pace. But for whatever reason, everything about this stage rubbed me the wrong way.

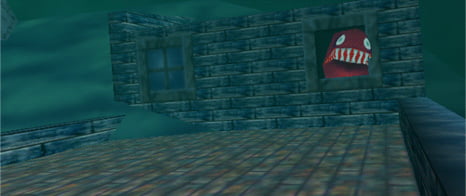

The music, as relaxed as it seems now, filled me with tension and dread. Its stark contrast from the upbeat bongos of other stages was off-putting. The level, which is embarrassingly simple when you look at a map, seemed to me like a treacherous underwater maze. Without my roll or jump, I was left with no means of defending myself against grinning chomps and spinning sharktopuses (sharktopi?). Until you find Engarde the swordfish, Coral Capers is more like a stealth mission than anything else, forcing you to avoid enemy patrols rather than confronting them head-on.

To six-year-old me, Coral Capers was uncannily creepy, and once it had claimed all of my balloons, I never returned. From then on, any time I came to a water level, I would pass the controller to my stepfather. I didn’t conquer my discomfort as I should have. I let it grow into an irrational fear.

My friend Chase had a different early experience with this phenomena, one that I would later come to share. When asked about it, he’s always quick to clarify: “I don’t have an irrational fear of water levels. I don’t have an irrational fear of anything in any video game…” He’s not being entirely honest, and he knows it. “Well, I take that back. Those fucking wolves.”

The wolves he’s referring to are the Colmillos from Resident Evil 4, who burst into tendrils of Las Plagas parasite when approached. He’s distrusted dogs in video games ever since, and while he doesn’t share my specific feelings about water levels, he knows this next example all too well.

Chemical Plant Zone

Chemical Plant Zone is the second set of stages in Sonic The Hedgehog 2, an industrial nightmare factory flooded with poisonous purple ooze. Above the surface, Chemical Plant Zone is fast and fun, featuring loops, tubes, and one of the best musical tracks in the Sonic franchise. But, as it is with any other 2D Sonic game, falling in water creates a sharp and dramatic shift in the gameplay experience. Where Sonic was once “rolling around at the speed of sound,” he is now clumsily struggling to move, fighting for his life.

“It probably stems back to when I was a kid,” Chase explains. “If [I] got stuck in that water, I couldn’t get out. I would always die and be like… ‘I’m done playing.’”

He’s not alone in his frustration. Much of the fun of the Sonic franchise comes from the fast-paced gameplay, allowing players to zip around each stage like a pinball. Sonic the Hedgehog underwater is almost an entirely different game. Like the Kongs, who lose their offensive capabilities underwater, Sonic is robbed of his greatest asset: his mobility. While Sonic can normally run and jump to escape a pit, underwater he is slowed to a crawl. And unlike the Kongs (who can seemingly hold their breath indefinitely), Sonic can neither breathe nor swim underwater.

This becomes especially hazardous in Act 2, where the player must climb a series of rearranging yellow blocks in order to escape a vertical chamber, all while the mysterious purple liquid is rising. “That’s the part I’m talking about!” Chase reacts. “If you get stuck down there, you’ll either drown, you’ll get crushed by those stupid blocks, or there’s a way that it’ll throw you back around and you gotta come back up the blocks again.”

I didn’t play Sonic the Hedgehog 2 until much later than Chase did, but even then this segment prevented me from progressing through the game, just as Coral Capers had done years before. Here the game takes an abrupt turn, plucking you from your high-speed adventure and tossing you to the bottom of a fight-for-your-life deathtrap, all set to the suspense-building tune of a quickening countdown. As an adult, this section is embarrassingly easy, but as a kid, I couldn’t handle it. I couldn’t deal. I put the controller down. I was done.

Ultimately, any discussion about water levels is going to touch on Ocarina of Time sooner or later. As we debated the origin of this childhood fear, the Water Temple was a recurring suspect, but was frequently dropped from our investigation. My friend Rhett had this to say:

“The temple itself wasn’t challenging to me. That wasn’t my dilemma. My dilemma was I already had my fear of water levels prior to playing the water temple. The part that stands out to me the most is that point in the Water Temple where you look down and there’s like, the dragon statue in the water? At first glance, that looked like a snake. I had to gather my thoughts.”

Wait, what’s this about a snake?

Jolly Roger Bay

Unagi the Eel is not a snake, but close enough. He lives in a sunken ship at the bottom of Jolly Roger bay, one of the earliest worlds in Super Mario 64. He isn’t one of the scariest creatures I’ve seen in a video game, but for a Mario villain, he is a little disturbing. Up until this point, the levels in Super Mario 64 had been upbeat and brightly colored, populated with enemies like Goombas, Bomb-Ombs, and Mr. Blizzards (they’re snowmen who throw snowballs, for Christ’s sake). Even the Piranha Plants and Chain Chomps are only mildly threatening by comparison.

Then there’s this guy, a dagger-toothed, dead-eyed creep who stands out like a Langolier in the Land of Ooo. His appearance is so jarringly inconsistent with the game’s artistic direction that his later incarnations had to be toned down. The Unagi of Super Mario 64 DS has had his mouth closed to hide most of his teeth, and his counterparts in Super Mario 3D Land have almost no teeth at all. And while these retroactive changes may have made the games more approachable for younger generations, they do nothing to numb the experiences of those gamers who faced the original Unagi as children.

My friend Rhett is one of those gamers—a man who was once a boy standing at the edge of Jolly Roger Bay. “When I first saw the eel—and give me a break here, ‘cause I was 7, 8, 9? Maybe somewhere in that area. So you see the big eyes, and you see the teeth, and that kind of freaked me out at first, but he was in the ship. I didn’t realize at this point what the obstacle was. I didn’t realize you had to lure him out of the ship.

“You get closer to him, and all of a sudden he comes out. That’s the part that really freaked me out. I can’t pinpoint what it is about that that freaks me out. It’s just the fact of being in a deep… thing of water, you know, where I’m having to hold my breath already, and there’s this giant-ass snake swimming around.”

And that’s all the eel does—swim around. He doesn’t even actively pursue the player, but accompanied by the helplessness and suspense that come with being underwater, Unagi’s presence alone is enough to ward off those who would fear him.

Rhett’s experiences in Jolly Roger bay stayed with him, preventing him from returning for all 120 stars until years later. Even today, Rhett is still somewhat anxious of swimming in water that he can’t see the bottom of—a fear he attributes to his childhood encounter with Unagi.

“It sticks with me to the point like—this literally happened to me two nights ago: I downloaded Mario Kart 7 on 3DS because it was my free platinum game from Club Nintendo. There’s a cruise ship level, and at one point in the cruise ship you can fall into some water, and I fell into the water, and that eel was swimming around. I was lying in bed with [my wife], and as soon as I saw that eel I was like ‘AAAAAAH!’ I had to pause for a second. Just seeing it—and I wasn’t expecting to see it—freaked me out, and I’m 27 years old.”

Following this revelation, I’ve made it a point to bring up Jolly Roger Bay any time I’m discussing the topic with new people. The sudden look of recognition on their faces is all the confirmation I need. “Jolly Roger Bay? Is that the one with the eel?”

This investigation began as a meaningless timewaster, born from the hypothetical midnight ramblings of people with nothing else to do on a Saturday night. I’d thought I could find the game responsible for giving us “videoaquaphobia,” and for a while I thought that game was Super Mario 64, but in gathering my arguments for this article I’ve come to understand too much about the nature of fear in games to blame a single example. Sure, Jolly Roger Bay is the least common denominator—the experience that the most videoaquaphobics I’ve known have shared—but it isn’t the root of the fear. That, instead, lies deeper.

Danger in a video game doesn’t make a game scary. After all, the danger in a video game isn’t real. You can be harmed, but you can’t be hurt. You can die, but you’re just going to come back anyway. So, to make a player feel endangered, you first have to make the player feel safe. Give the player enough agency to overcome the game’s artificial dangers in fun and exciting ways. In time, the player will master these challenges and find comfort in these abilities. Then, when the time is right, take these abilities away. Restrict the player’s agency when he or she is the most vulnerable. Make the safety feel real, then pull the rug out.

The water levels from my childhood have done on accident what a good horror game does on purpose: restrict players of their agency. Donkey Kong Country lets you jump and roll to fight Kremlings, then makes you sneak around helplessly in underwater mazes. Sonic the Hedgehog 2 lets you accelerate to insane speeds to escape hazards, then slows you down when the pressure is on. Super Mario 64’s experimental 3D controls become treacherous underwater, when you need your maneuverability the most. In these levels, being underwater means being in twice the peril, with half the power.

Children can be very impressionable when playing video games for the first time. A bad experience with one element of video gaming can result in a lifelong distrust of that particular convention. In my case, as it is with many others I know, water levels are full of bad experiences, and they’ll stick with us for the rest of our lives. And while I may not lose any sleep over Unagi the Eel, it sure makes for an interesting conversation.

I know this post is Uber old but I really wanted to get this out. It’s 2016 now and Far Harbor for Fallout 4 just came out, and I bought it. Awesome right? Well ever since i was 6 I have been afraid of video game water, although in 2D scrollers it isn’t… so bad. But I digress. Far Harbor is an amazing map and all but about 40-50{54aa50b9c141fdc6877fe76dd9617d72386c166c2b8f2ba44b2c6137e789c1e0} of it is… water. On top of all that some of the best loot is IN THE WATER, as in sunken ships and stuff. Now I don’t know if you have played Fallout but the water in it you can hardly even see in as it is irradiated and the one thing that makes me feel safe, power armor? You sink straight down and have to walk the ocean/lake/pond floor to make it across. I have only gotten in the water twice on purpose and both times I was hyperventilating and at one point almost threw up.

NOPE.

But for real, that makes me REALLY want to play Far Harbor now!