The aesthetic strategies of Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days in expressing a documentarian style and commenting on our relation to images.

Replaying Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days, I find myself often reminded of the rich discourse in film culture following the rise of inexpensive digital video aesthetics in the early 2000s. While low-grade and crude at the time, digital video became a worthwhile tool for artists like Michael Mann and David Lynch who adopted the crude format to make visually abstract, often confrontational, works. Films like Miami Vice or Inland Empire experimented with what the technology could do, showcasing longer shadows, overexposed lighting, more vibrant colors, grainy nighttime footage, extreme focal lengths, and more fragmentary editing patterns achieved with computer programs. IO Interactive’s 2010 game Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days is, in many respects, an undervalued masterpiece drawing from this artistically expressive moment in cinematic history and was woefully shunned by a video game culture too reactionary and shortsighted to engage with it.

What Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days presents is an abstract catalogue of death and misery with Cormac McCarthy-esque levels of lyrical bleakness. I’ve written at length about Dog Days before, having published a piece on the game’s rough and nihilistic surrealism for Unwinnable, but this game demands greater examination given the depths of its engagement with a slew of themes, artistic influences, and narrative risks. In certain stretches of gameplay, Dog Days emits a heavy, atmospheric gloom during shootouts so that action feels poetically forlorn and languid, like a funereal pall hanging over the proceedings. Other times, the game favors the brash immediacy of bodily flesh and movement, touting impressionistic images that emphasize blurred textures over straightforward dramaturgy and visual clearness.

REAL AIN’T PRETTY: THE DETAILS

Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days has a basic story, but I get the feeling that IO was more concerned with chiseling an urgent work of art than drawing clean narrative lines. The game follows the titular characters reuniting in Shanghai, China, after settling down and following a more mundane lifestyle. Their domestic bliss is cut short when they provoke a gang war and lawless manhunt after playing a role in the unforeseen killing of a corrupt politician’s daughter with ties to the local mob. Dog Days stands apart as one of the most concise statements of video game violence and evil, elaborating on the themes of predecessor Dead Men with greater success in a self-contained, standalone story. It’s also a game about images and our relation to it; Dog Days presents an unparalleled aesthetic of snuff film-esque, low-grade home video footage as though captured on a cheap cell phone. These are images that exist in the same intellectual headspace as filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard who crafted similar painterly smears of pixelated light and color in late works Film Socialisme or Goodbye to Language. The implied presence of an unseen camera operator following Kane and Lynch throughout the game adds a layer of remove from the atrocities committed onscreen, trailing a legacy of similarly minded video games like Manhunt and Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number.

If the game evoked such artistic influences and promoted themes as deep and varied as I’ve argued, then why did Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days suffer the mindless, negative groupthink it faced upon release (and often still does)? Kane & Lynch in general was plagued by a number of factors, including the shallow criticism that Dog Days was too short and had unpolished shooting mechanics, but most infamously, its predecessor was marred with the firing of writer Jeff Gerstmann for giving it a mixed review score. That’s a controversy that has only entrenched mainstream games criticism and the discussion about “ethics” further into moronic mudslinging (a general discourse embarrassingly intensified with added misogyny in the past year and a half), and I’m uninterested in examining the matter further.

Instead, I’ll suggest that the unwarranted critical failure of Dog Days had more to do with a games culture ill-equipped with the language to talk about the game when it was released in 2010. Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days is very much a mass-market art game, employing its imitation of blown-out digital video to provide a strange new texture underutilized in video games. Of course, mainstream discussion on games as art was only in its nascent stage in 2010. Roger Ebert’s now archaic diatribe against games as art was published that year, prompting serious discussion and online talking points. Even today, many gamers and some critics still resist the kind of critical dialogue necessary in considering games as art, shunning pertinent topics like feminism, gender politics, and race representation and generally refusing to engage with a broader political and social landscape in favor of cultural isolationism.

We were also still mired in the useless drivel that was “ludonarrative dissonance,” a narrow-minded, counterproductive means to talk about games that merely lambasted works with the buzzword rather than analyze how dissonance between gameplay and narrative can operate on thematic and stylistic levels. Mainstream games criticism only recently stepped up conversation with the release of Spec Ops: The Line in 2012 and Brendan Keogh’s book-length analysis Killing is Harmless, prompting (directly or indirectly) further reconsideration of games that attempted similar thematic concerns as Spec Ops like Far Cry 2, Max Payne 3, and Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days. These are games in which the dissonance between a narrative’s condemnation of violence and gameplay’s complete embracement of it produces thematic tension that clues players into the fragmentary psychology of the characters onscreen. To simply fault games on the basis of “ludonarrative dissonance” disallows for engagement with crucial narrative devices like unreliable narrators, metafiction, and Brechtian distanciation techniques. It disengages video games from how other mediums like theater or literature handle dissonance, cutting off games criticism from useful language that could better serve underappreciated and divisive games.

Refreshingly, a number of eloquent defenses that identify the bold artistic strategies of Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days and its complex themes have steadily emerged over the years since its release, and these writings greatly inform my thoughts here. Max Chis’s seminal piece on Dog Days as an anti-shooter achieving similar themes as Spec Ops: The Line notes IO’s storytelling triumph as prophetically ahead of its time, praising it as “perhaps one of the most ingenious AAA games of recent memory, and nobody noticed or cared.” His essay is vital for those looking to uncover a long-form response to the game’s lack of appreciation, joining some other necessary essays delving into Dog Days’s deliberate, confrontational ugliness and nihilism regardless of their personal liking of the game. Of further importance is Filipe Salgado’s entry in the essay anthology Shooter, its presence alongside writings on established genre works like S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Far Cry 2 which grant the game additional critical validity. Finally, Ed Smith, one of the few writers who gives marginalized games like the Kane & Lynch series a fair shake with thoughtful analysis, notes how predecessor Dead Men (and by extension, Dog Days) is a valuable work because of its refusal to provide neat catharsis or clean moralizing, thus making the game “truly about bad guys, truly about violence.”

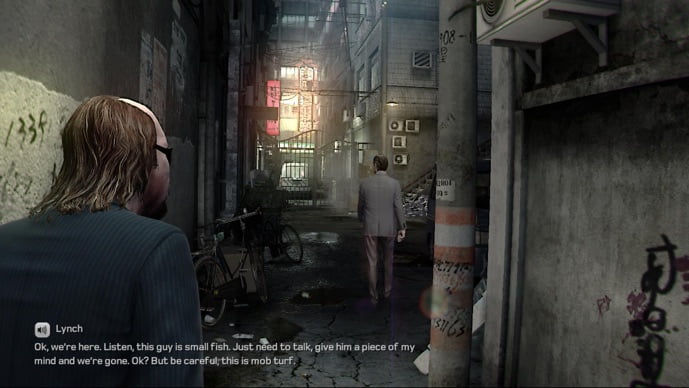

What we can observe over the course of five years since the release of Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days is an initial, reactionary contempt that set the tone for discussion and an eventual reconsideration by a small but growing handful o f writers. Dog Days, to this particular writer’s eyes, remains a singular vision that pulls the merits of video game art into greater focus. From the moment its pair of damnable nightcrawlers reunite to their Orphic descent into the pits of the Shanghai underworld, Dog Days steeps us within an aesthetic all its own, its setting of neon-drenched urban squalor and reckless subterfuge affirming the inevitability of violence.

THE WORLD’S FIRST DOCUMENTARY SHOOTER

Even before the game begins, Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days prefigures its thematic interest in digital video culture and our knotty relation with images in its main menu and loading screens. The randomized looped video that plays against the main menu signals the subjective, home video-style handheld camera presentation throughout the game. The images provided are that of candid normalcy that disguises the malicious horrors to come. A camera positioned from a car’s backseat idly gazes out the window as Chinese radio pop warbles from the dashboard. In another, the camera eyes a spider web tangle of telephone lines, and a jumbo airliner descends close to the city. Whatever the provided imagery, the constant presence is an overcast sky that establishes the gloomy atmosphere of the game and a misdirecting sense of mundane domesticity that the game inverts over the course of its narrative.

The loading screens extend these thematic and stylistic interests, displaying still images appearing consecutively to form a collage like a Facebook album of vacation photographs. In lieu of a loading bar, Dog Days centralizes a YouTube-style buffering wheel that suggests that the entire game is a kind of prerecorded, home video snuff film that we’re queuing up to watch. Indeed, the very first image we see when the game loads is that of a close-up of a digital camera in the midst of recording. This expressive first shot is already significant because it connotes a moment of reflexivity, calling attention to the game’s means of expression and in a way, turning the camera on audiences like a similar shot pulled in the opening scene of Jean-Luc Godard’s film Contempt. Moreover, the camera emphasizes a layer of remove from reality; our protagonists are claustrophobically framed in its tiny viewfinder and obscured by pixilation rather than depicted directly. A series of impressionistic, quick cuts witnesses the flash of a knife and a voice crying out, “I’ll fucking kill you!” before the game cuts to its title.

Within the first few seconds of Dog Days, we’re already tuned into its disorienting, fragmentary aesthetic of low-grade digital video. As previously stated, what sets Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days apart from its predecessor (and most other games) is its stylized, voyeuristic camerawork. The game presents its world through a glitch-prone, pixelated digital camera operated by an invisible third party following Kane and Lynch throughout the game. As such, the game takes on a vérité aesthetic that feels paradoxically real and unreal. The camera shakes wildly when you sprint forward, evoking a sense of rushed shakycam like bystanders filming on the ground guerilla-style. The camera’s “lens” is occasionally speckled with blood, dirt, and grime, adding a level of smeared materiality to the screen that grounds the game to a sense of realism as though the camera is slowly getting worn over time.

Inversely, the visual styling of the game also underscores a level of falsity that increasingly breaks apart the digital image. Shadowy locales intensify the graininess of the image as the camera struggles to focus on a light source, and lens flares from car headlights and streetlights create a blinding sheen. Throughout the game, the camera sometimes glitches in pixelated error, conveying a smeared digital hell of blown-out pixels and characters coming out of focus. Nudity is pixelated out as though manipulated in post-production to make it appropriate for online upload. Enemies dead from headshots will also be pixelated as though their corpses are too gruesome to bear, evoking censored newsreel footage or snuff films that conceal the identity of those murdered. This aesthetic degradation extends to the audio of the game as well. Extremely loud noises such as explosions or a burst of crazy gunfire will produce tinny, low quality audio as though the recording equipment is faltering.

These stylistic flourishes contribute to a general sense of visual and auditory pollution that attacks our senses. Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days’s handheld, found footage-style presentation lends itself to a snuff, documentarian style that resists the typical video game appeals to “fun” and “enjoyment,” instead favoring aesthetic ugliness and disruption. Curiously, early marketing concepts dubbed Kane & Lynch 2 as “The World’s First Documentary Shooter,” and the full spread of the advertisement campaign and its unpublished ideas are just as gripping, emphasizing bodily decay mediated by digital camcorder aesthetics. The marketing team’s labeling of the game as a documentary shooter is a striking interpretation that further cements the notion that there is indeed an invisible camera crew following Kane and Lynch through the streets of Shanghai.

If we are to accept this documentarian understanding of the game, then Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days uncannily follows in the tradition of the great 1992 mockumentary film Man Bites Dog, a work with a similarly canine-inflected title and preoccupation with taped ultraviolence. The trio of directors Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel and Benoît Poelvoorde depict a fictional documentary crew filming and eventually becoming complicit with the crimes of a crazed serial killer. The overlap between Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days and Man Bites Dog is astonishing, from the way in which both films stake a claim in documentarian realism in depicting criminality to the finale of both works where the camera operator is knocked down as though fatally wounded.

Translating a “documentary shooter” style to gameplay creates a strange effect to our point-of-view. In a way, Dog Days asks the player to control two characters simultaneously: a third-person view of Lynch and an implied first-person view of the unseen camera operator, both movements tethered to one another. The presence of a digital camcorder filming these events means we’re viewing everything through a mediating screen that disengages us from the immediacy of the characters’ atrocities. As in snuff films, the game portrays extreme violence enacted on others and on the self, and the layer of remove provided by the implied camera suggests a critique on video game violence by resisting immediate identification with the characters and events onscreen.

SHANGHAIED

To move through Shanghai in Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days is to experience a markedly ugly urban landscape that reflects the damaged, rotting psychology of the characters. Kane and Lynch are detestable murderers not meant for players to admire, and the setting provides a visual exteriorization of their inner moral decay. The occasional glimpses of domestic bliss like in the apartment of Lynch and his girlfriend Xiu suggest a kind of ironic relationship wherein the evil and the mundane coexist in a means that conveys the former’s latent ubiquity in the latter.

Much of the game takes place in polluted back alleyways or dingy interiors that make for an oppressive and aggressively unpleasant visual landscape. Dog Days barely provides any natural light, setting Kane and Lynch’s campaign in ungodly nighttime hours. Light sources are often artificial, including garish fluorescent bulbs and the dead glow of neon that casts strange colors. There are sequences at dawn, but the sun overhead shines a ghostly white light that feels as far away as the sun from Mars, providing not warmth but coldness.

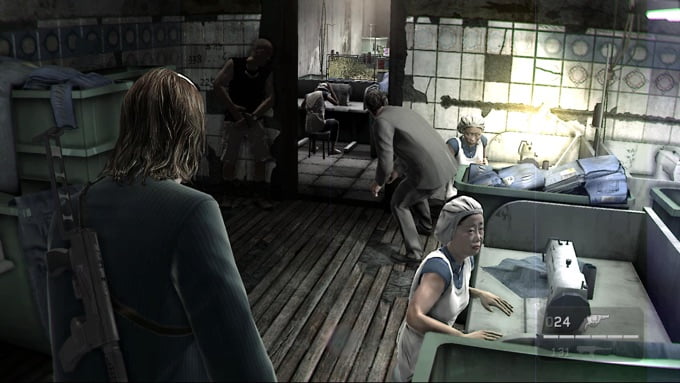

Seeking shelter inside yields no respite from the game’s all-consuming purgatorial hell because you’ll only encounter labyrinthine interiors that all look similar. There’s a controlled chaos in the game’s representation of a tangible criminal underworld. Narrow passageways and a maze of dank, cluttered back rooms provide numerous dead ends, conveying a sense of bewildering claustrophobia that envelops all who descend deeper. Criss-crossing electrical wiring hangs overhead as though it’s delivering a suffocating chokehold on the city. Dog Days rarely steps foot in the touristy, glamorous avenues of Shanghai, but in the underbelly: storage areas, sweatshops, alleyways, freezers, black markets, slums. The tight, meandering alleys crowded with debris, tepid water, and black trash bags encircled by flies reminds me of the slums of the Kowloon Walled City. As in Max Payne 3, Dog Days has a secondary interest in visualizing the exploitative effects of rampant capitalism and political corruption on working class peoples. Traversing a sweatshop, you’ll stumble upon a dark, windowless room with bunk beds tightly packed together to house its workers, and the environment feels prison-like.

Of course, you feed into this problem too, perpetuating organized crime and gun violence within these spaces. One particularly memorable location is a seedy electronics store peddling cheap DVDs and consumer electronics, a blaring neon sign dripping red and pink visual pollution outside. This is an underground economy that exchanges violence and material goods; two-bit criminals cohabit the same streets as honest day laborers.

Kane and Lynch will also tread the dilapidated periphery of these urban spaces, crossing construction and demolition sites where the essence of a building lingers. Rotting tenement blocks lay amidst the cratered ruins of concrete pillars and rubble sandwiched between the oppressive cityscape. Time and time again, you’ll advance through downed sections of pipe, through ditches, and between pillars like vermin emerging from beneath the earth. The brighter neon lights of more respectable parts of the city are always on the horizon and tantalizingly out of reach.

These construction sites are especially unusual because they feel borderline fascist in their oppressively industrial and sharp concrete edifices. Indeed, these ubiquitous spaces warp into abstract landscapes under the grotesque vision of Dog Days. Shootouts in construction zones appear sculpturally organized, enemies weaving around concrete pillars, steel blocks, and metal pipes in geometrical precision. These industrial surroundings recall the minimalist sculptures of artist Richard Serra. They’re ultimately chest-high walls, but Richard Serra and Kane & Lynch 2 share similar themes of industrial severity and the flow of people through inorganic spaces. That a video game even evokes abstract sculpture warrants closer inspection to foster the cross-pollination of disparate artistic traditions.

Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days offers abundant thematic and stylistic questions for game critics to probe, yet the series’ unwarranted derision accumulated over the years reflects a medium still regressive and repellent to the idea that games should be engaged on a serious level. That a genre shooter game from the bargain bin can entertain complex themes and abstract artistic flourishes should lead us to believe that more exploratory works detached from generic conventions must be even more artistically cohesive and venerable. However, the mainstream critical narrow-mindedness in writing about a game from a lowbrow, easily accessible genre like a shooter suggests that games culture would be severely hesitant—even resistant—in engaging on a deeper level with more obviously arthouse works. This reality is failing the artists making these games, and so the antidote would be to reconfigure the way we write about video games and the way we think about the games themselves. To look forward into the future of video games necessitates that we also look back—back to marginalized works that would benefit from a second shot at critical analysis now that we’re at least better than we once were. Kane & Lynch 2: Dog Days is one such game, and I’m more than eager to step back into its bleakness, and to disappear once more into its darkened heart.

Most realistic depiction of getting a six-star wanted level since Postal 1

Thank you so much for this. This game is something truly special that deserves being talked about and you said it so well.

Thank you thank you.

Thank you for this!!! The game is a peace of art. One of a kind. A brilliant, magical experience. Actually, as a big fan of underground cinema I started to think while ago that game industry just doesn’t have a space between AAA hits and indie – a space in which I could place Dog Days, which would be for artists who can work with last-gen technology and create art-house stuff. Dog Days tried that and failed. It’s a shame that they had to close the series, actually I would love to play K&L3 in Suda51 style concept. IOI!!!

An interesting write-up but I don’t appreciate the notion that Kane & Lynch 2 was secretly a really good game and the critics (and players) who thought otherwise at the time of release were just too stupid to understand it.

Kane & Lynch 2 is bad. It’s an awful game. It’s buggy, poorly scripted, and incorporates incredibly basic and badly-executed gameplay mechanics. It’s just not a particularly enjoyable game, and no, that’s not an intentional by-product of the developers trying to teach you that killing isn’t supposed to be fun, it’s just because it’s a lazily-made game. It’s pretty apparent, playing the game, that not a whole lot of effort or even passion went into this project.

I share your enthusiasm for the hyper-bleak tone of the game and the visual effects, but that’s about it – the actual execution was terrible. K&L2 had the potential to be something special in the hands of a competent development team, or at least one that cared, but clearly after the failure of the first game, any enthusiasm IO had for K&L withered up.

K&L2 is complete dead weight. There are times when I really, really wanted it to be good, but it just isn’t. And while the game is certainly quite unique in its style and perhaps deserves to be talked about for it, it’s not a game that needs to be re-evaluated as a hidden masterpiece. Future developers who want to take a page from K&L2’s book (and I doubt there’s many) should look at how to salvage it rather than imitate it.

Honestly, I think it’s easier to fall in love with the idea of K&L2 rather than the game itself, and that is the trap that its defenders fall into.