Playing The Silver Case is like looking through a window into the mind of Goichi Suda (AKA Suda51) and those at Grasshopper Manufacture.

Though the individual aspects that comprise the game are not in themselves new, but as a gestalt, arriving in the West 17 years after it first came out in Japan, it comes across as remarkably unique. However, this uniqueness will not be for everyone; Suda51 games are still known for their tendency to be divisive, and what better example than the first game from his own studio Grasshopper Manufacture.

For those familiar with the work of Suda51, The Silver Case will likely feel like the missing piece, the piece that helps bring them closer to understanding the absurd world that he has created. Playing the game now gives the impression that it is filled full of references from past games, when conversely it is The Silver Case that actually spawned these very references in the first place. In terms of gameplay (if you can call it that) it shares very little with the action horror games that Grasshopper Manufacture – and by extension Suda51 – is currently associated with. That is not surprising given that the last game Suda51 actually directed was No More Heroes (way back in 2008) but he has been responsible for aspects such as the story, character design, and the script, with gameplay choices left to those he deemed more capable than himself (as explained in a recent interview with Eurogamer). This is why elements like Suda’s fascination with the moon – a constant visual marker in The Silver Case – was still present in 2013s Killer Is Dead, directed by Hideyuki Shin.

No More Heroes marked the shift for Grasshopper Manufacture towards the over-the-top violent action games that it is currently known for, but Suda’s personal output has mostly favoured slower paced games of an investigative nature. Killer7 was his first game to reach the West, and whilst it does feature first person shooter elements and a health system, it is not too far removed from the control scheme of The Silver Case, due to its reliance on an on-rails movement system. However, even though movement in The Silver Case is managed in this way, it is incredibly limited. Most of the game is in fact ‘navigated’ via text boxes.

The Silver Case is a visual novel/text adventure, and this is an example of a genre signifier being entirely accurate. Whilst other games in the genre allow for player interaction and the illusion of choice, The Silver Case makes almost no attempt of giving the player control over the narrative that is unrolling – at what can sometimes be seen as a glacial pace – for it retains control of how and when events will proceed. That’s not to say that there are no interactive elements at all, for there are some puzzles, but the door based puzzles have (in this remaster) been provided with buttons giving automatic solutions, and the two instances that required tools from the item inventory require no thought at all.

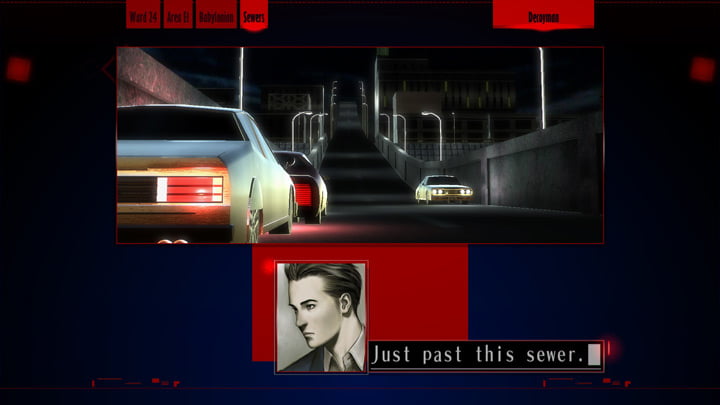

All is forgiven though, because the presentation is phenomenal. The Silver Case is not something that equates to a book that has been put onto a screen accompanied by some music and images. Instead, it utilises what it refers to as the ‘film window’ system, originally designed to add visibility of the text during the PlayStation 1 days, but also has the added benefit of giving more creative control to the director. This creative control over text, images, and video is what makes The Silver Case stand out as well as making the experience feel interactive, even though, for the most part, it is not.

Unsurprisingly for a visual novel, the story is the focus, but The Silver Case makes the engaging decision to split the narrative into two parallel pathways. The whole set up works in a similar way to a TV mini-series where each episode focuses on a specific case, while coming together to tell the overall story. Complicating matters, the two parallel pathways are literally that, as the game is split into scenarios; ‘Transmitter’ cases (written by Suda51) and ‘Placebo’ reports (written by Masahi Ooka and Sako Kato). The former is the main narrative drive focusing on player named silent protagonist, AKA ‘Big Dick’ (no, really) and the latter follows investigative reporter Tokio Morishima, who unravels the mystery from behind the scenes.

The two scenarios overlap, with ‘Placebo’ expanding upon the events that took place in ‘Transmitter’, and characters from both also appearing in the other scenario. At first this approach is quite jarring, which is possibly intentional, but it is an effective way of explaining aspects of the story and even revealing key story points without distracting from the pacing of a given case of ‘Transmitter’. Unlike ‘Transmitter’, ‘Placebo’ sticks to a more continuous narrative but is heavily impacted by the events that have unfolded in ‘Transmitter’. Not a lot actually happens in ‘Placebo’ for the most part; it is an exploration into the life of Morishima and interacting with his pet turtle Red. The main functions of the reports primarily revolve around checking his emails, yet the life of Morishima gets under your skin. Even though there are times where he is a deplorable person, he can also be oddly relatable, and his feelings for Red particularly stand out. This aspect, combined with the fact that most of the text here is given via an internal monologue through an electronic diary, makes it feel like something from an early Murakami novel.

The titular ‘Silver Case’ unsurprisingly features throughout the game and in particular the ‘Transmitter’ scenario, but it is the quest to understand the truth from the facts regarding the killer Kamui Uehara that drives the overall narrative forward, with Morishima also tasked with finding out any information he can about Kamui. Despite the overarching focus of ‘Transmitter’ revolving around Kamui, there are other stories that the cases focus on that on the surface seem completely disjointed, but in their own way relate back to the mystery that surrounds the existence of Kamui. It is during these cases that the player becomes more familiar with the supporting cast of characters, who are all seemingly hiding something. Immediately Sumio Kodai stands out, bringing a straight edged demeanour to the situations and is somewhat reminiscent of Twin Peak’s FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper. As the game progresses, however, it is Tetsugoro Kusabi, who despite initially coming off an archetype of the hard-boiled detective genre, elevates the moments in which he is present.

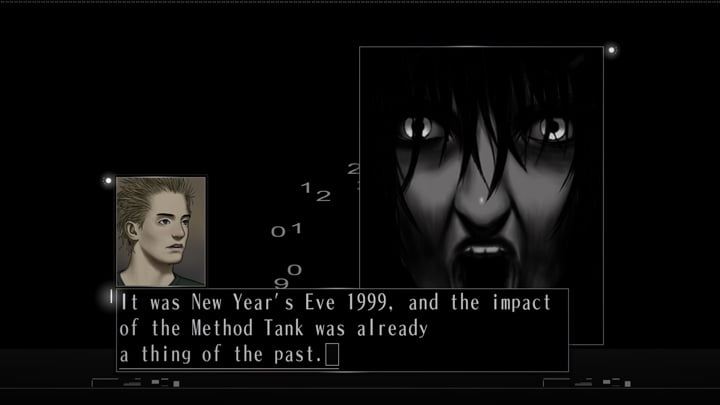

There are times where the plot can be hard to follow, especially when the game is referring to the different security units and political factions, all of which use acronyms that contribute to the confusion. Yet these are secondary pieces of information, as it is the character development that takes the forefront, as well as the individual stories that interweave these developments. This sees the game tackle some pretty weird stories, without ever fully succumbing to going completely off the wall. This is aided by the sporadic use of anime cutscenes (which will be familiar to players of Killer7) as well as live action footage (also incorporated into the intro for loose sequel Flower, Sun, and Rain). The latter is particularly noteworthy, as it is one the elements that was purposefully not properly updated for this remaster. It provides a depiction of Japan from 1999, and to alter the footage would detract from that authenticity.

Despite utilising anime and live video to help drive the narrative, the majority of the visual elements are via the use of wonderfully drawn stills with equally expressive character profiles overlaid on top during conversations. What’s also impressive is that the art style differs between ‘Transmitter’ and ‘Placebo’, inferring that the player is seeing the world through a different pair of eyes. These drawings also surprisingly manage to work in collaboration with the 3D locations often in the background, helping to reinforce the disconnect between the world. The relevancy of this being that there are characters in The Silver Case questioning their reality, and even those who do not question their reality on an existential level still question the truth based on the ‘facts’ they are provided with. Information is where true power lies, and it is a tool used by different factions to achieve their aims. For a video game created in 1999, its interpretation of the Internet and its role in society is eerily prophetic, with most of the depictions of its use still relevant today and not feeling outdated.

The music of The Silver Case deserves mention; given the length of time the player spends reading through text, it does an excellent job at helping the pacing and preventing the game from getting monotonous, adhering to the older adage of looping scores that do so without getting tiresome. It also provides tension and intrigue to scenes where needed, but its core tracks have such brevity and perfectly encapsulates the noir themes of the game. The Silver Case is composer Masafumi Takada’s second project working with Suda51 and it is fascinating hearing his early work, given that you can hear tiny fragments that have later been expanded in later scores that he has worked, especially those for Grasshopper Manufacture. The sound effects found in the game also make frequent returns in later Grasshopper games as well, which rather than simply being cost effective, is what contributes to the aesthetic style that one equates to the work of Suda51/Grasshopper Manufacture. They even managed to make the constant clicking sound of a keyboard that chimes every time text is displayed on the screen sound pleasing.

It is interesting to review such a game, because it is very difficult to do so in isolation, for it is now viewed under the pretext of the wider output of work attributed to Suda51. Some of the themes explored in The Silver Case reappear in Killer7, and the overall tone is not too dissimilar. This is also the case with pseudo-sequel Flower, Sun, and Rain which shares characters. Likewise, it is because it cannot be viewed as an independent piece that it is easier to know whether or not this is a game for you. Whilst it is more grounded than the utterly bizarre Killer7, and more straight forward than the at times downright incomprehensible Flower, Sun, and Rain; The Silver Case can be seen as the source for these more creative endeavours. That’s not to say that The Silver Case is not creative, nor is it exactly conventional within its genre, but it seems to be more aware of the line into peculiarity and walks confidently along it.

In The Silver Case there is the line, “The imperfect can be considered perfection due to its imperfection,” and this might just be the best way to describe it, and many of Suda’s games as a whole. This is not a game that will appeal to everyone, mostly because at times it feels like calling it a video game is a bit of a stretch. However, its story and presentation can negate this criticism and make it a memorable and unique experience. Due to its conceits to enable the player to proceed with the story makes it one the most technically accessible games from Grasshopper Manufacture.

Finallllyyyy, this is the perfect review of TSC we needed.