Recently, a single image with a handful of words on it was circulating on social media. And it’s been bugging me. Gnawing at me. But I finally figured out why.

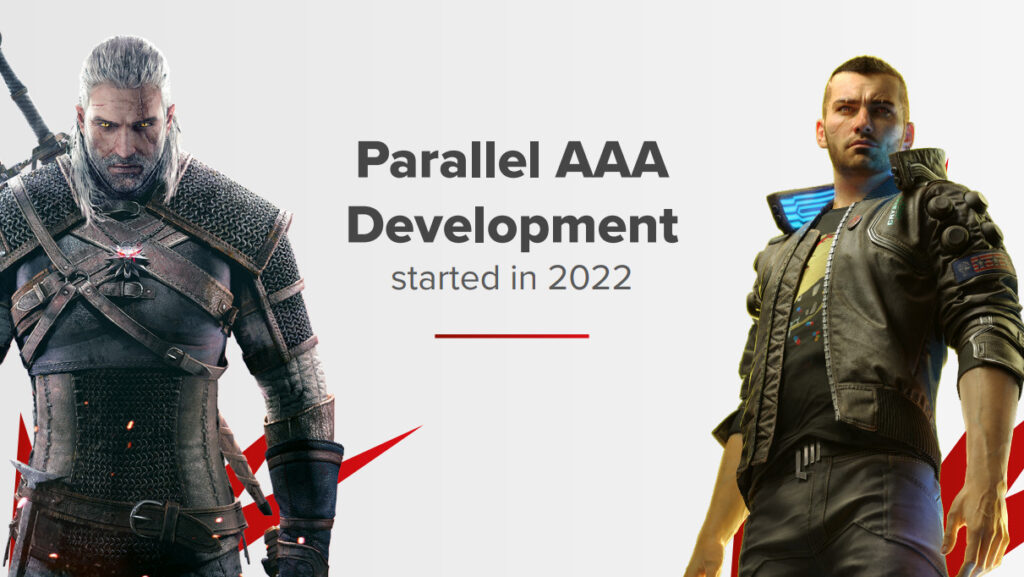

That image’s origin: CD Projekt Red, the Polish developer and publisher of The Witcher and Cyberpunk video games, and master of the screenshotted text image. But far from its usual waspin apology, of black text on yellow background (the colours of serial apology-requirer Cyberpunk 2077), this single text image was seen as something more positive. At least, on the face of it. It was certainly unusual.

The image was a slide taken from a PowerPoint deck, titled “Strategy Update: Long Term Product Outlook”, released to accompany a YouTube video of the same name. In it, various high-ups at CD Projekt Red proceeded to outline exactly what the company is working on, including:

- The Witcher

- Project Sirius – a new game in The Witcher universe, developed by CD Projekt Red subsidiary studio The Molasses Flood

- Project Polaris – the first of a new sequel trilogy to The Witcher, developed by CD Projekt Red, with its two sequels set to release within six years of the first game

- Canis Majoris – an open-world RPG, developed by a third-party studio featuring some Witcher veterans

- Cyberpunk 2077

- Phantom Liberty – a Cyberpunk 2077 expansion, developed by CD Projekt Red

- Project Orion – a sequel to Cyberpunk 2077, also developed by CD Projekt Red

- New IP

- Project Hadar – a completely new game currently at the concept stage, also being developed by CD Projekt Red

Which is stark contrast to pretty much every other major development studio or publisher in the world, in which the very existence of games is usually a preciously-guarded secret, lest it become another Beyond Good and Evil 2 or Skull and Bones. (Sorry, Ubisoft, but you don’t do yourselves any favours. Duke Nukem Forever also sprang to mind but that one released, eventually, so Beyond Good and Evil 2 is the new high watermark for interminable development.) Until the recent leaks, Take Two and Rockstar refused to even admit that Grand Theft Auto VI – the most nailed-on sequel that has ever been nailed on in the history of nailed-on sequels – was in development or that it even existed, such is the drive for secrecy on unannounced projects.

Much of this comes down to the marketing cycle around video games. The goal, if you’re out of the loop, is to cultivate a nebulous thing called “hype”, to nurture its growth and fan its flames, until it reaches the point of pretty much consuming everything. Alarming as that sounds, that’s basically a marketing success in AAA video game terms. And anything that risks the impact of that marketing push when you want to drive “hype” – from secrets being revealed beforetime or footage that doesn’t look entirely favourable, right through to even acknowledging the existence of a game that hasn’t been officially announced – is nothing short of disaster.

On the face of it, then, CD Projekt Red’s decision to get out ahead of the “hype” cycle and announce its games in advance seems… quite sensible? Mature, even? This is a developer and publisher laying out its stall, telling its fans (and its shareholders) exactly what to expect, and roughly when, from its development teams. It certainly sucks the early oxygen out of the nasty “hype” fire that consumes the development and marketing of so many games. This is a move that is antithetical to the video game marketing playbook, and shows that perhaps CD Projekt Red is learning lessons from the boastful, edgelord marketing / repeated delays and poor eventual performance / black-text-on-yellow-background screenshotted apology loop of Cyberpunk 2077’s beleaguered release.

But there’s a word in there that’s troubling me. Re-read that sentence again, and see if you can spot it.

“This is a developer and publisher laying out its stall, telling its fans (and its shareholders) exactly what to expect, and roughly when, from its development teams.”

“… and roughly when…”

When. In this context, it’s enough to drive fear into the hearts of video game developers. And, sure, CD Projekt Red doesn’t lay down a precise timeline for all the games in that strategy update, but it does at least promise that it will be releasing a full, three-game Witcher sequel trilogy over a six-year period. Let’s assume that most of the mechanical work is done in the first game, and that can take as long as it needs to before the clock starts on that six-year window. And even if we assume the third game in the trilogy releases on the final day of the sixth year, with games of the size and scope of The Witcher, that’s still an enormous amount of content, resource, and development time. For context, Rockstar and Bethesda, the nearest comparable studios for games of this scope – with their Grand Theft Auto/Red Red Redemption and Elder Scrolls/Fallout release cycles, respectively – puts out one of these brobdingnagian open world epics every five or six years at most. CD Projekt Red is promising three of them in six years, plus a Cyberpunk 2077 sequel, and a bunch of other stuff to boot.

And CD Projekt Red does not exactly have a glowing history when it comes to scoping, time-planning, and project managing games of this size. Studio co-founder Marcin Iwiński – who recently, through the medium of screenshotted text on Twitter, announced he was moving from co-CEO to chairman of the board – famously promised that crunch on Cyberpunk 2077 would be non-mandatory and “more humane” than on previous projects, alluding to the allegedly horrific crunch endured by staff working on The Witcher 3 that was, judging by Iwiński’s own choice of words, presumably not very humane at all. And then they made it mandatory anyway.

If I was a developer at CD Projekt Red looking at that slate of games, I would be feeling very nervous. While the fatuous “hype” cycle is inane and immature, at least if your company is keeping its releases secret, there’s no public-facing expectation to deliver anything to a timescale. You shouldn’t have to crunch to meet a deadline on a game that hasn’t even been announced, let alone given an actual, publicly-known release date. (And to be clear, it feels like I’m picking on CD Projekt Red here, but it is by no means the only company that crunches. There are horror stories wherever you turn, like 100-hour weeks at Rockstar or hospitalisation at Naughty Dog to the simultaneous project crunch that probably did for Telltale Games in the end, to name just a few.)

So, what is the answer, then? If companies keeping games secret leads to an unpleasant “hype” cycle, but companies announcing things early risks excessive crunch to avoid publicly missing targets, how do we solve the problem? The only answer I can come up with is consumer action. And to see why it works, we have to look outside the games industry altogether, to a completely different sector: chickens. Or, more specifically, egg farming.

In the UK, as in the rest of the world, battery-farmed eggs were the norm. In battery production, hens are caged with no ability to leave that environment; in some cases, with barely any room to move at all. They are housed in their tens of thousands. They will never feel sunlight on their face or grass under their feet. They have no environmental enrichment and peck each others’ feathers out, or their own, out of stress, or boredom, or both. All they do is eat, shit, lay eggs, and sleep. That’s it. That’s their entire existence. The aim? To produce cheaper eggs. Not a desire to be intentionally cruel; just that simple, capitalistic notion, to drive costs down and maximise profit, dressed up as consumer-friendly cost savings.

In spite of campaigning from animal rights groups, there was no expectation that would ever change, until TV chef Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall burst into tears at a battery farm filming a documentary for Channel 4 almost 15 years ago. That’s not to overstate the importance of Fearnley-Whittingstall’s documentary against years of campaigning by organisations and individuals for more humane egg production, of course, but it’s that sort of dramatic, glass-shattering moment that sparks change in consumer society. “Did you know it only costs 9p more to produce a free-range egg than a battery one?” People would ask. “Oh, absolutely, I’d totally pay 9p more an egg to avoid those sorts of horrific scenes,” came the obvious response. And it’s all good and well to say those sorts of things to friends, a spot of water cooler virtue signalling with no intention to follow through, but do you know what? People actually did. They shifted to free-range eggs in droves. Over time, responding to consumer demand, supermarkets moved to selling only free-range eggs in shells. Some, the more ethically-minded like Marks and Spencer and the Co-op, went one better, and took the far more difficult step of rooting out battery-farmed eggs in their baked and packaged products. Even McDonalds, that towering totem of clown-faced capitalism, has switched to free-range-only eggs.

But the market only changed because consumers changed their behaviour, and consumers only changed their behaviour because they became aware of something that was happening, behind closed doors, in their name, under the auspices of securing them a lower price at the checkout. The corporate machine was assuming we would prefer enormous, industrial-scale suffering for the sake of 54p on half a dozen eggs. And, for once, the corporate machine was wrong.

So why is it, then, we’re more prepared to change our behaviour on the welfare of animals – from battery farming chickens to cruelty-free cosmetics – than on the treatment of actual human beings in the creation of video games? It’s not like we haven’t had enough reports on working conditions, the equivalent of Fearnley-Whittingstall’s documentary, from the likes of Jason Schreier, Matt Kim, Megan Farokhmanesh, and others. In the eyes of the fans, it often comes down to the notion of free will, that while the chickens didn’t choose to be put in cages or the bunnies to have cosmetics dropped into their eyes, game developers actively choose to work at the companies that crunch. Or that because it’s the industry standard and everybody does it, that it’s just accepted practice and will never change. There’s the falsehood that, because developers are being paid, then the conditions are not in fact abusive at all – doubly so for CD Projekt Red who, controlled by Polish labour laws, has to pay overtime to its crunching staff – but that simplistic worldview is entirely missing the point. There’s even the idea that working in video games is such a dream job (for the angry YouTubers and armchair commentators) that game developers should gladly swallow any and all conditions thrown at them for the “honour” of working on a game like Cyberpunk 2077.

We, as a society, are generally prepared to accept this capitalistic norm – at least, until we hit that glass-shattering, sobbing in a chicken farm moment of realisation – if it benefits us in some meaningful, material way. That’s particularly telling in the current cost of living crisis in the UK, where niceties like humanely-produced eggs might fall to the wayside in the wake of soaring prices. Yes, people will buy the battery-farmed eggs because they’re “cheaper”. Yes, people will buy the tested-on-animals cosmetics because it’s “safer”. Yes, people will shop at Amazon (where warehouse employees have to pee in bottles to avoid missing fulfilment targets) because it’s so “convenient”. But what benefit is it to us, the consumer, if video games are developed under crunch conditions?

As far as I can tell, absolutely none. There are no benefits to us, the consumers of video games, in making game developers crunch. The price of games isn’t coming down, like with battery-farmed eggs – in spite of the fact they’re getting more work out of not enough staff. Nor is the quality of games going up as a result of crunch – people tend to produce poorer work with more mistakes when they’re exhausted, in fact. The only benefits are for the corporations, in that they can stretch too-few developers further to cover for failings in production and project management, rather than increasing the development budget and, therefore, reducing the profit margin. And these are targets that, for the most part, are kept secret from consumers until much later in the development process, don’t forget. If you’re crunching before your deadline is public, that’s doubly stupid. That’s one of the precious few benefits of the “hype” cycle, the idea that you don’t need to crunch until your public-facing deadline is approaching, which is why the very public announcement of CD Projekt Red’s massive impending workload is of particular concern for a developer so prone to extreme crunch.

The thing is, it’s not actually that easy to consume games ethically. In fact, it’s surprisingly difficult. We might want to avoid games that were produced under terrible conditions for moral and ethical reasons, but if a video game is seen to be a commercial failure, it’s always the developers who suffer, not the bosses. Boycotting Activision Blizzard games might feel like an act of solidarity with striking staff, for instance, but the outcome of those boycotts might be taken out on the very workforce that sympathisers are hoping to support. Do you buy the game to support the developers, but end up tacitly supporting the method in which it was produced? Or do you avoid the game on principle, but risk the livelihood, even the continued employment of the people who created it?

Outside of a few worker-owned co-ops, there are no guarantees that a video game is produced humanely. We’re sadly missing the free range label on eggs or the leaping bunny mark on cruelty-free cosmetics to tell us at a glance that a video game was developed crunch-free. (I have long advocated for one, and even considered starting such a campaign, but it’s damn-near impossible to figure out how to assess and police the thing. Answers on a postcard if you figure that one out, please.)

But while it isn’t obvious which games were produced without crunch, it’s often painfully obvious which games were, and until we, the consumers, start voting with our feet – and, more importantly, our wallets – the corporate machine is going to keep assuming we’re fine with crunch. That it’s a practice worth continuing because we’re still buying the games tainted by crunch, which is a level of acceptance that, to the corporate bean counters, looks suspiciously like approval. Vindication, even. That we’re fine with people sleeping at their desks, not showering for days, missing out on family moments, ruining their health, and in some extreme cases, literally working themselves to death to make video games.

Video games, of all things! I really hope that we’re not all fine with it. I know I’m not. Most of all, I hope that we, as consumers with enormous influence over decision making with our collective spending power, can send a message to video game developers and producers that crunch is never acceptable.